Two Westerns Directed by Monte Hellman

A look back at The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind.

A brief introduction to Monte Hellman, the importance of Roger Corman, and an unfocused meander down film lore’s path

Monte Hellman (1928-2021), like many filmmakers of his generation (including Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and Jonathan Demme), began his filmmaking career under the auspices of Roger Corman, who gave him his first job as director on Beast from Haunted Cave (1959). Throughout the 1950s, Corman had been helping to fund Hellman’s Los Angeles theatre company. Hellman had been interested in theatre from a young age, but also harboured aspirations as a filmmaker. Before Corman eventually steered him onto the filmmaking path, his only other experience in the field had been as an assistant editor for ABC TV, an unfulfilling job that urged Hellman to set up his stock company while he was waiting out his eight-year membership with the Film Editors Guild. Once he’d done his eight years with the Guild -- whether actively working or not -- he could move up from assistant editor to editor.

During the short time his theatre company was working, Hellman staged Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, at that time only the fifth production of the play in the world and the first in L.A. When the theatre was converted to a cinema, Corman saw this as a sign that Hellman should pursue his calling as a filmmaker, and so Beast from Haunted Cave was born.

Following this, Hellman was tasked with expanding three other Corman pictures along with Beast so they could be sold to television. These were Ski Troop Attack (1959), Last Woman on Earth (1960) and The Beast from the Haunted Sea (1961); trademark Corman quickies for sure, shot solely to turn a fast buck, but also a crash course in the rudiments of filmmaking that Hellman put to further use as one of three directors (the other two being Corman and Coppola) on 1963’s The Terror.

The Terror was an unexceptional Boris Karloff vehicle, a kind of embarrassing cousin to Corman’s celebrated Poe cycle that has nonetheless achieved almost mythical status. This is due chiefly to the film appearing in Peter Bogdanovich’s debut feature proper, Targets (1968) as the film-within-a-film Boris Karloff’s disillusioned horror movie actor looks back on ashamedly while he simultaneously looks ahead to a future peopled with the likes of Tim O’Kelly’s homicidal sniper. Karloff agreed to make the film as deferment for not being paid for The Terror. It would be his final role. Life imitating art, a brief sidestep away from Hellman’s story, and a bitter-sweet chapter in film lore’s story.

But back to Hellman.

In 1964, after the debacle/learning curve of The Terror, Hellman set off for the Philippines to shoot two more pictures for Corman, Back Door to Hell and Flight to Fury. Hellman took along Jack Nicholson, whom he’d first met on the set of The Wild Ride (1960), and then again on The Terror. As well as starring in both films, Nicholson also wrote the screenplay for Flight to Fury. Hellman worked flat-out, sleeping sporadically for around five hours a day, cutting one film while he shot the second, until an undiagnosed tropical disease hospitalised him. However, these two pictures cemented Hellman and Nicholson’s working relationship, and after an earlier script they’d collaborated on together was rejected by Corman, their producer and mentor suggested they make a western. Ever the economist, Corman told them, “As long as you’re making one, you might as well make two.” These would be Ride in the Whirlwind and The Shooting, the former written by Nicholson, The Shooting by Carole Eastman (under the pseudonym Adrien Joyce), with Nicholson and Hellman producing. They were shot back-to-back in 1965.

But before we delve into these two, let’s continue on our brief journey through Hellman’s career.

After Ride in the Whirlwind and The Shooting were sold to television, Hellman continued to work for Corman, taking on work as an editor on Peter Fonda’s Easy Rider prototype, Hell’s Angels on Wheels (1966), before directing two more Corman features, the road movie Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) and Cockfighter (1974). These latter two starred Warren Oates, who also appeared in The Shooting and who would go on to star in Hellman’s third and final western, China 9, Liberty 37 (1978), completing a run of director-star collaborations with Oates that equalled Sam Peckinpah’s use of the actor throughout his own career.

From the 1980s through to the new millennium, Hellman would direct only four more films, but as is evident throughout his career, he was of as much importance working on other people’s projects as he was his own. In between directing, he was brought in to recut Peckinpah’s The Killer Elite (1975), worked as a second-unit director on Robocop (1987) and executive produced Quentin Tarantino’s blistering debut, Reservoir Dogs (1992) after Tarantino found himself in a position to direct the film himself following the sale of his screenplay for True Romance.

It’s a rich tapestry, with players like Nicholson, Oates, Corman, Peckinpah, Tarantino, and countless others coming into the fray, pursuing their own paths, and acknowledging Hellman’s influence on their careers. In many ways, he reminds me of John Milius, directing a clutch of impressive films, but embellishing other filmmakers’ projects along the way. And though Two-Lane Blacktop is regarded as his masterpiece, of the films he made for Corman, from Beast from Haunted Cave to Cockfighter, his two westerns remain, for me, his best.

The Shooting

Due to its banishing of the usual ‘white-hat/black-hat’ tropes that define the western, its skewed deconstruction of western mythology, and its refusal to be pigeonholed (is it a revenge story?), The Shooting has been labelled as both an acid western and an existential nightmare. As a study in existentialism, it hits the mark, though, for me, the label ‘acid western’ doesn’t quite seem to fit; it doesn’t display any of the religious iconography or LSD-soaked imagery of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo (1970) or Dennis Hopper’s The Last Movie (1971), but it does, in the final scene, present that thing which must always be avoided on an acid trip: staring at your own reflection.

Hellman has stated that his films have all, in one way or another, been informed by Samuel Beckett. Since Waiting for Godot in 1957 (which Hellman staged as a western), he’s returned to the ongoing cyclical search repeatedly, starting with The Shooting up until his final film, Road to Nowhere in 2010. The questions of “who are we?” and “where are we going?” abound in the closing shot of Ride in the Whirlwind and the endless, open road of Two-Lane Blacktop, yet through the character of Willett Gashade (Warren Oates) in The Shooting, the questions are given a voice.

The film begins with Gashade returning to the mining camp he ran with his partners: his brother Coigne, the dim-witted Coley (Will Hutchin) and Leland Drum. He learns from Coley that Leland has been murdered, possibly in retaliation for the accidental killing of two people in town, one of whom is described only as a “little person,” possibly a child. The man responsible (Coigne) has fled the camp. When an unnamed woman (Millie Perkins) appears and hires Gashade to escort her to a town named Kingsley, Gashade accepts, with the proviso that Coley can come along too. She refuses to reveal both her name and the purpose of her journey, and soon Gashade begins to suspect that she is searching for his brother. As they journey, Gashade notices a stranger tailing them. He eventually reveals himself to be Billy Spear (Jack Nicholson), a hired gun who has a connection to the woman. As three become four and the journey takes them further into the desert, the possibility of finding Coigne becomes greater as the vast, open spaces begin to expose his tracks. By the end of the trail, Gashade and the audience are given a denouement of sorts, but it’s one that raises further existential questions whilst simultaneously stating its purpose.

At the start of the film, Gashade is seen resting his horse by a watering hole. He looks nervous, scanning the surrounding landscape for signs of whoever is following him. He’s seeking answers, and though his demeanour suggests he feels threatened by his invisible assailant, he doesn’t try to hide his tracks, instead laying a trail of salt for his pursuer to follow.

The pursuer, who reveals herself to be a woman, puts to rest in Coley any thoughts of being gunned down. Her slight frame, pretty features, and child-like petulance are something to be coddled. While Coley’s attempts to woo her are met with scorn, Gashade observes her behaviour in an attempt to piece together her intentions; is she in some way connected to the accident that led his brother to flee (the mother of the “little person,” perhaps), or does she hold a personal grudge against Gashade, who’s only mention of his activity away from the camp is that he made a living briefly as a bounty hunter. As Gashade observes her, he notices how many times she shoots her pistol up into the air, treating it as though it were a toy and even levelling it at Coley’s face when his pestering becomes unbearable. It’s only with the appearance of Spear that her demeanour changes, and her verbal abuse gives way to a cold detachment that matches her male counterpart.

The power play between the abusive woman, the thoughtful and reasoning Gashade, and Coley, the simpleton who naively believes his acts of chivalry can win the woman’s heart, is given extra weight with the appearance of Spear; on one side, the woman and her hired hand clearly hold all the power, while on the other, Gashade carries Coley, ever ensuring his safety against the bullying Spear. Yet, as their journey progresses and the landscape begins to dwarf them in a series of wide shots, the desert becomes the great equaliser, blurring the lines between predator and prey, leader and follower.

It is during this point in the film that The Shooting is at its most Beckettian. The absurdity of following a woman into a desert without being given a solid reason is parlayed by Gashade, whose hesitancy forces the woman to increase her offer of payment. Her willingness to do so goes some way to confirming Gashade’s suspicions that the woman is hell-bent on revenge, and he follows in order to prevent a possible murder, the absurdity being that the murder may be his own or Coigne’s, who, it is later revealed, is his doppelganger.

When Coley’s horse succumbs to the heat, forcing the party to abandon Coley in the desert, he meets a man with a beard, seemingly lost, and offers him a stick of candy; Coley’s intentions are as good as ever, but rather than saving the man from the heat, the sight of his sucking on candy only highlights the absurdity of the situation. As the man waits for death, the offering of something as sweet as candy is a bitter irony he can take with him to the grave.

Hellman doesn’t abandon Western tropes in favour of ambiguity, instead allowing them to run side-by-side. The ending features the stand-off and a kind of resolution, but without a clear explanation of the woman’s plight that is usually followed by the road back to civilisation. The fight between Gashade and Spear is clumsy and over with quickly, contrasting the measured, low angle stand-offs of the Sergio Leone films that were drawing appreciative audiences, who lapped up a fresh take on the western as seen through a foreign lens throughout the 1960s. The grainy, slow motion killing at the end of The Shooting, edited in such a way that it serves to blur the lines further, kicks back at the crisp, wide angle placement of the shooters standing at opposite ends of the screen. By its end, we can never be one-hundred percent certain that the woman has been killed, or Coigne, or Gashade. The only person who may ever know for sure is Spear, who we see in a closing shot reduced to a stumbling stick figure without a horse as he approaches the scene, his own fate sealed by the indifferent landscape. These are people whose pasts are never fully known to us. With the possible exception of Coley (who recounts events to Gashade in a flashback), they appear without introduction, and so it is only fitting that their lives should end without an outro; as Spear struggles to advance upon the scene, ‘The End’ title prevents his arrival.

Ride in the Whirlwind

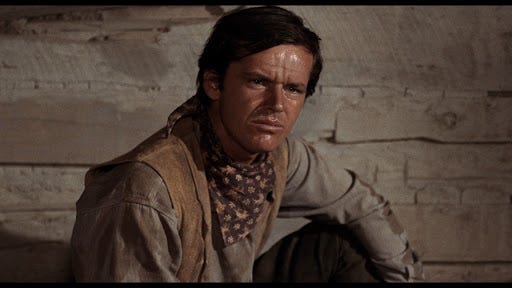

Ride in the Whirlwind stars Cameron Mitchell, Jack Nicholson and Tom Filer as Vern, Wes and Otis, three cowhands who find themselves accused of taking part in a stagecoach robbery. After the actual perpetrators of the crime (led by Harry Dean Stanton’s Blind Dick) are hunted down and hanged by a vigilante group, and Otis is killed in a shoot-out, Vern and Wes try to find refuge in a farm belonging to a family of three: husband and wife Evan and Catherine and their daughter, Abigail (Millie Perkins).

It’s the simplest of stories typical of a B-movie oater, giving plenty of opportunities for Hellman to stage gunfights and melodramatic interplay between the accused and the family. But this a Monte Hellman western, and as in The Shooting, the characters and situations are tools which he can put to better use skewering his own view of familiar genre tropes.

To give Nicholson his due, his script, with dialogue sourced from letters and journals from the time, is of as much importance as Hellman’s sparse direction in highlighting the plight of these two men. In contrast to the wonderfully playful vernacular of Eastman’s dialogue for The Shooting (Coley: “I don’t give a curly-hair, yellow-bear, double dog damn if you did”), the dialogue in Ride in the Whirlwind is spoken awkwardly from the mouths of illiterates (Wes, on discovering the guilty hanging from a tree: “Man got hanged”). Their inability to articulate adds to the hopelessness as the two men futilely attempt to prove their innocence. What makes their predicament more terrifying is that their accusers are a vigilante mob, armed to the teeth and all too willing to shoot first without giving a care as to who or who is not innocent.

A hint of the absurd is also evident in the outcome of Ride in the Whirlwind; Vern and Wes, innocent of a crime, are forced to commit horse-theft and murder as the net closes in, an irony to match Gashade’s murder (if he was murdered) being a direct result of him trying to prevent one.

As elusive as it is simplistic, Ride in the Whirlwind predates many of the films that heralded in American counter-culture cinema, and it’s telling that both this and The Shooting garnered more critical appreciation in France before finally being released theatrically in the U.S. after Nicholson hit big with Easy Rider in 1969. Like that film and others of its kind (notably Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and The Wild Bunch (1969)), it displays a cynical look at how injustice can prevail and paints the law, whether it be judicial or of the land, as criminal. When Wes rides off into the sunset, he does so without a rousing score to assure the audience that his inherent goodness will be paid in kind. One strongly suspects that sooner or later he’ll be gunned down like Bonnie and Clyde in their car, the Wild Bunch on Bloody Porch, and Billy the Kid and Captain America on the backroads of the deep south.

Two of the greatest westerns to come out of an era when the genre was all but dead in America, The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind bridge the gap between the psychological aspects of Anthony Mann’s westerns in the 1950s and the far out insanity of bona-fide acid westerns like El Topo, Greaser’s Palace (1972) and High Plains Drifter (1974) that emerged in the decade that followed them.

![Ride In The Whirlwind – [FILMGRAB] Ride In The Whirlwind – [FILMGRAB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!AvJb!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0c7ff379-ddd2-4514-83e4-efb4acd9b766_1280x696.jpeg)