Ten Ozploitation Classics You'd be a Drongo to Miss

Reviews of ten Australian films from Wake in Fright to Next of Kin. Part of April's Pulp and Schlock series of stories and essays.

For a country that produced the first recognised feature length film with Soldiers of the Cross (1900), and had public screenings within a year of the Lumiere brothers’ first public screening at Paris’s Grand Café in 1895, Australia’s contribution to cinema underwent a prolonged period of inactivity that saw it floundering while American, European and Asian cinema thrived.

During an initial boom period that produced 150 features during a twenty-two year period (a huge amount for the time), and of which over two-thirds were made between 1910 and 1912, Australia’s cinematic output was placed on a temporary hold due to the outbreak of World War I and the country’s heavy involvement in it. The Combine, a 1913 merger between exhibitors, producers and distributors, has been considered to be the cause of a further decline in Australian-produced films, with distribution and exhibition of overseas imports crowding out homegrown, independent filmmakers. By 1923, American films had begun to dominate Australian theatres.

The following decades were kinder to Australia’s film industry: Cinesound Studios operated successfully throughout the 1930s and into the early 1940s, Kokoda Front Line! was a joint winner at the 1942 Oscars, and homegrown talent like Errol Flynn, Chips Rafferty, Peter Finch and Rod Taylor began to make waves in both Britain and America. Yet, their fame abroad meant there was little interest in seeing them in Australian roles, and soon the industry found itself lacking any notable leading men. Adaptations of Australian works of literature were also the product of British and American film studios, and as the 1960s loomed, Australia found itself floundering once again in the shadow of rival film industries.

By 1970, the Australian film industry was all but non-existent, and it took a new wave of filmmakers including Peter Weir, Everett De Roche, Richard Franklin, and George Miller to capitalise on the support being offered from the Australian Film Development Corporation. Together, they heralded in what is now considered the Golden Age of Australian cinema. Their films were by turns weird, loud and nasty, and encompassed horror, science fiction, period drama, and action. Termed ‘Ozploitation’ films by Quentin Tarantino, they helped boost an industry that went on to produce hits like Crocodile Dundee (1986), Dead Calm (1989), Romper Stomper (1992) and Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994). Here are ten of the best.

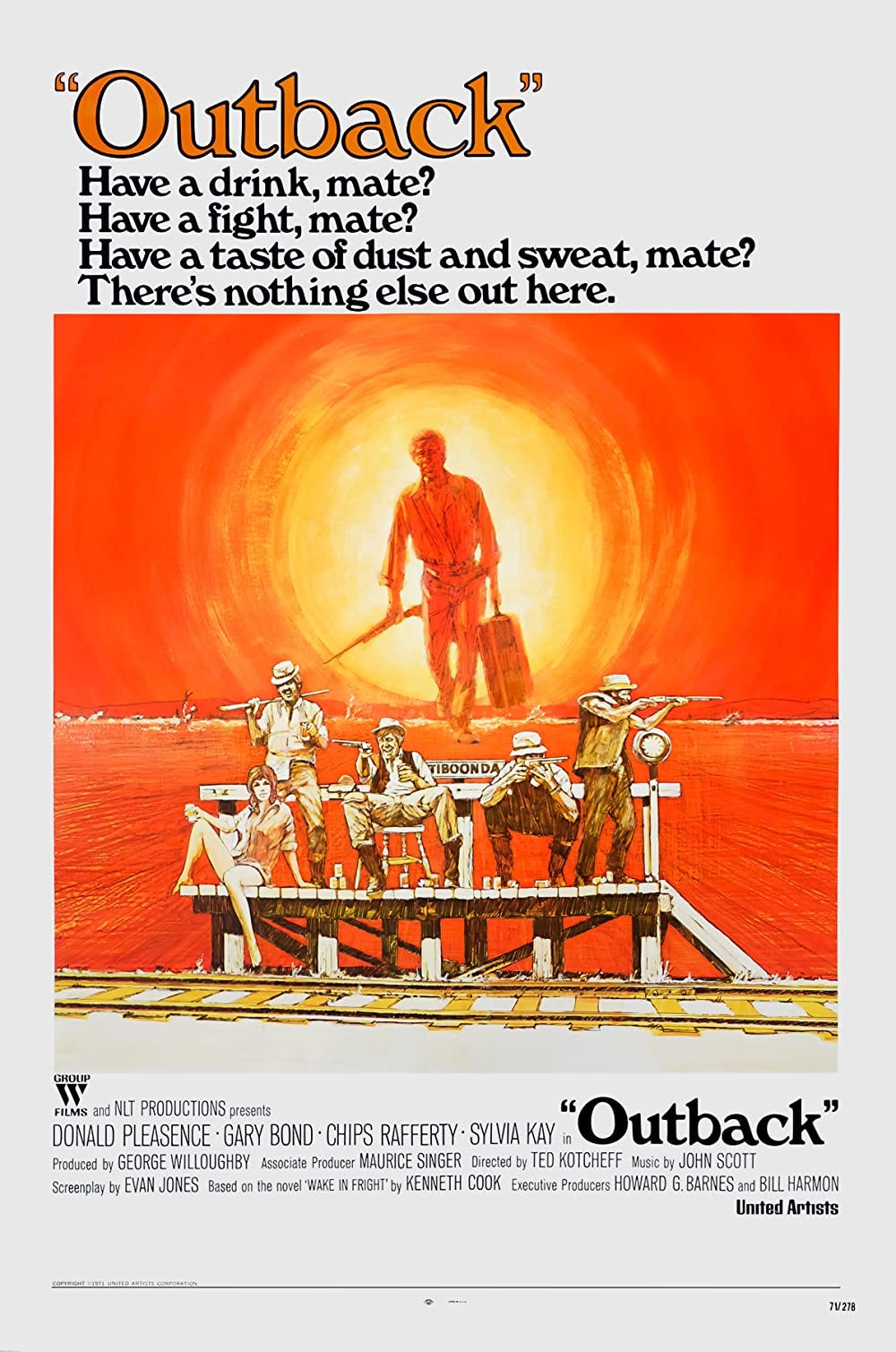

Wake in Fright, a.k.a. Outback (dir. Ted Kotcheff, 1971)

Released the same year as Nicholas Roeg's Walkabout, Wake in Fright was released as Outback outside Australia, and the film fared better internationally than it did on home soil. Gaining a cult following over the years, the sought after original uncensored negative was discovered in the mid-90s in a shipping container marked for destruction. The digital restoration process that followed returned the film to its original glory, but retained the opening grainy shot: a 360° circular pan of Tiboonda, a town surrounded by nothingness bar a school house, hotel and train station platform.

Gary Bond plays John Grant, a pompous English school teacher who leaves Tiboonda to spend Christmas in Sydney with his girlfriend. Stopping at Bundanyabba for a connecting train, he becomes trapped by the locals' overbearing hospitality and habit of forcing beer on him at every opportunity, namely policeman Jock Crawford, played by Chips Rafferty, whose lack of an uvula enabled him to down an average of thirty pints during a day's shooting without slurring a line.

Instructed by Canadian director Ted Kotcheff to avoid cool colours, Brian West photographed everything, from the clothes, buildings and landscapes in hues of orange, yellow, red and brown. The effect is stultifying, mirroring the slow deterioration of Grant as the heat and alcohol grind him down.

Encountering Doc Tydon (Donald Pleasance), an alcoholic doctor who continues to practice in "The Yabba", Grant goes from one drunken episode to the next, sweating alcohol out of his pores almost as fast as it’s forced down him. Machismo tinged with an underlying homosexuality further confuse his mindset, until a primal inner self breaks through to the surface in a shocking scene filmed during an actual kangaroo hunt (Kotcheff and his crew had to fake a power cut to curtail the hunters who shot, skinned and beheaded kangaroos).

Essential viewing, but not for the light-hearted, this should be your first port of call as an introduction to Australia’s new wave.

The Cars That Ate Paris (dir. Peter Weir, 1974)

The residents of a small town in Australia (the Paris of the title), cause car crashes, recycle the car parts, and subject the victims to psychological or medical experiments depending on the severity of their injuries.

With a premise like that, this could have been a great little film, but the ideas are never fully realised. Told largely from the point of view of Arthur (Terry Camilleri), the softly spoken survivor of a crash that killed his brother, the film kind of meanders along without any direction.

Reasons to watch are few, but here they are: A funny scene that spoofs Sergio Leone's westerns — in his new role as parking inspector, Arthur, helped by the town's policeman, faces down a gang of outlaw drivers who have driven through the mayor's garden ("We're talking about pot plants. Smashed pot plants."); it also holds the same fascination for welded together car wrecks that George Miller displayed in his Mad Max films; and a cardboard cut-out tribute to Chips Rafferty (the policeman from Wake in Fright, who died before the film premiered) can be spotted if you have a keen eye and know who Chips Rafferty is. Other than that, there's not much going for it.

A comedy horror that's neither funny or horrific, it's of interest for being Peter Weir's debut feature.

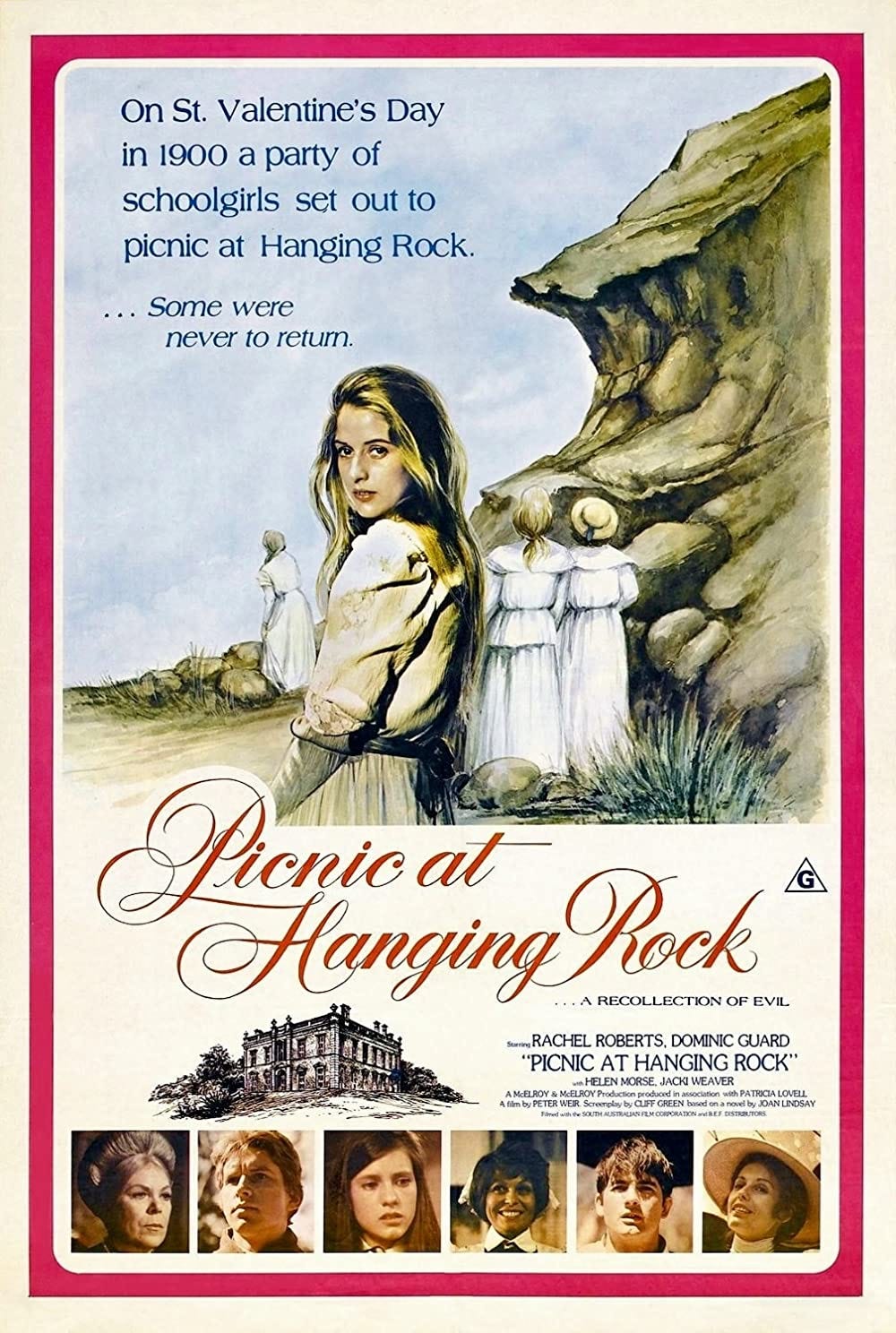

Picnic at Hanging Rock (dir. Peter Weir, 1975)

The second feature by Peter Weir, Picnic at Hanging Rock is based on the 1967 novel by Australian author Joan Lindsay. Though the book was a work of fiction, in her foreword Lindsay asked her readers to decide for themselves whether the story was fact or fiction, leaving it widely open to interpretation and debate, so much so that it became a part of Australian folklore.

The story, about the unexplained disappearance of four schoolgirls and their maths teacher during a picnic on St. Valentine's day in 1900, is impossible to pigeonhole. Is it science fiction, a murder mystery, a commentary on women's liberation at the turn of the century, or all three?

When Weir met with Lindsay, the author told him she would never reveal the answers to the questions she raised (she wrote an explanatory chapter and edited it out of the book before it was published). Weir respects this by doing the same, instead using symbolic imagery and random thoughts spoken out loud ("It's as though the rock's been waiting a million years for us." / "Everything begins and ends at the exactly the right time at the right place.") The maths teacher, meanwhile, is shown reading an equation where two points meet to form a solution, the picnicers' watches stop at 12pm while the amplified ticking of clocks continues in the 'real' world, and there are multiple shots of the girls reflected in mirrors. There's also an emphasis on virginal white and, of possible significance later, blood red.

Shot by Weir's regular cinematographer Russell Boyd, veils of varying thickness were draped over the lenses to give the film an ethereal, other worldly quality. The first 40 minutes that lead up to the disappearances is a masterclass in hallucinatory, dreamlike filmmaking, combining slow motion, dissolves and natural light. The only other films from this period I can compare it to aesthetically are Barry Lyndon (1975) and Days of Heaven (1978).

Hard to believe this was the same filmmaker who gave us The Cars That Ate Paris the previous year, it has the same meticulous attention to period detail and customs evident in Weir's later films, such as Gallipoli (1981), Witness (1985), Master and Commander (2003) and the underappreciated The Way Back (2010). A beautiful, eerie experience.

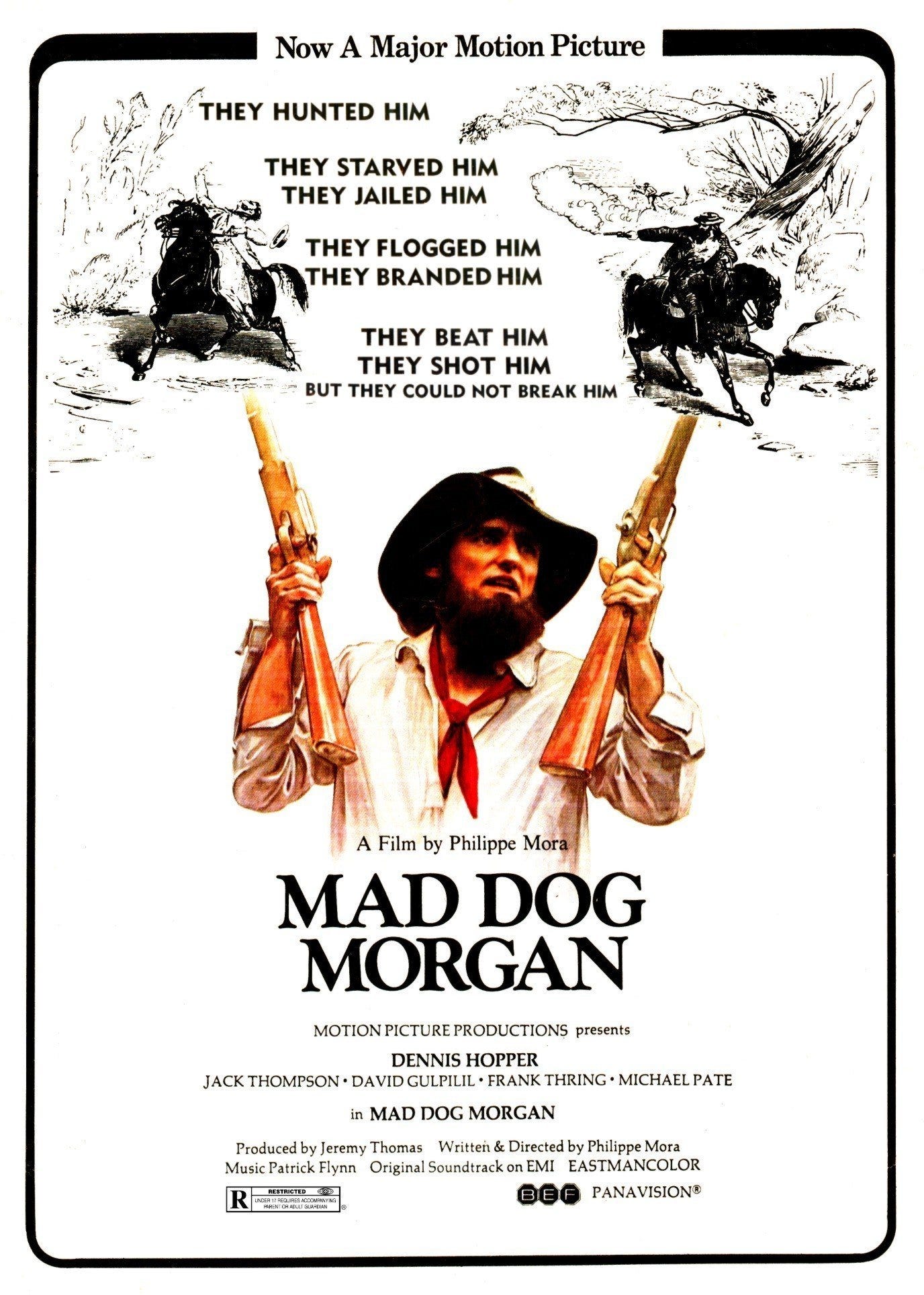

Mad Dog Morgan (dir. Philippe Mora, 1976)

Mad Dog Morgan is based on the life of John Owen, later known as Daniel Morgan, a bushranger who robbed and murdered settlers and authority figures in the mid-19th century. His murder at age 35 gave him immediate folk hero status.

Shot on a small budget, Philippe Mora's biopic is rough around the edges in the way Sam Peckinpah's mid- to late-70s output is. It falls short of matching Peckinpah, but it's still a very good film, helped no end by the appearance of Dennis Hopper in the lead role.

Filmed during Hopper's almost mythical 20 year period of drug and alcohol dependency, his performance is both fiercely intense and somewhat pitiful. Like Hopper, Morgan was a product of both the environment and times he was born into, a thorn in the side of a staid establishment whose rejection led to both men going into self-imposed exile — Hopper in New Mexico, Morgan in the bush.

Clearly inebriated in some scenes, Hopper improvises lines and actions that add to Morgan's hair-trigger personality, the actor embodying the role further by speaking in an Irish accent on set, and refusing the bathe, much to the chagrin of the costume department. With his costumers threatening to strike, Mora stepped in, telling Hopper that Morgan bathed regularly in the Murray River, conveniently situated behind where Hopper was standing. Keeping in character, Hopper ran fully clothed into the water.

Though co-star David Gulpilil claimed Hopper to be a "mad bastard," and admitted to being high himself throughout filming, somehow the whole thing stays stitched together by fast cuts, usually when Hopper's improvisations look as though he might be straying into a chemically induced ramble. Despite his problems, he still delivers a great performance, setting the tone for the string of maniacs he'd go on to play in later roles.

Good support comes from Frank Thring as Superintendent Cobham, a personification of the authority figure who looks like a cross between Alfred Hitchcock and Blofeld. Typically great line: "I want his spleen on my desk."

Well worth a watch, especially for Dennis Hopper, but also for Gulpilil playing a mean didgeridoo and the best burning man stunt you'll see outside of mainstream cinema.

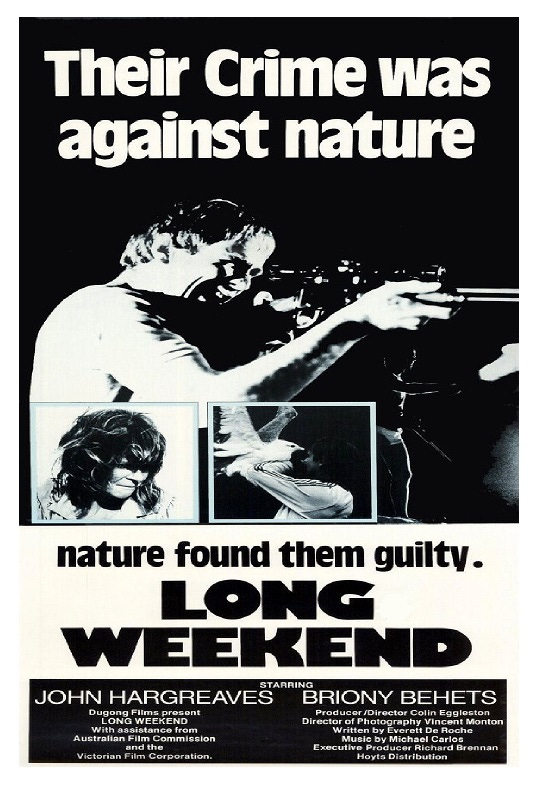

Long Weekend (dir. Colin Egglestone, 1978)

The first film to be scripted by Everett De Roche, who would go on to work with Richard Franklin as well as writing the Ozploitation classic Razorback in 1984, Long Weekend stars John Hargreaves and Briony Behets as an unhappily married couple on a camping trip at a secluded beach. Their disdain for each other is matched by their disrespect for nature (flicking cigarettes without a thought for bushfires, littering, chopping into trees for no apparent reason), and soon enough nature becomes very pissed off indeed.

They're a pretty unlikeable pair, and a steady drip feed of backstory makes them more so whilst at the same time drawing just enough sympathy from the viewer to forgive them, unlike nature, which is completely indifferent and just wants them to fuck off back to where they came from.

Weirdly, this has been overlooked until recently, while lesser 'nature takes its revenge' films of the time, like the woeful Day of the Animals (1977) and The Swarm (1978), seem more well known. Much better than you'd expect it to be, it's tense, well acted, and especially well scripted. The ending is fantastic. Highly recommended.

To read more on Australian cinema’s eco-horror sub-genre, click here.

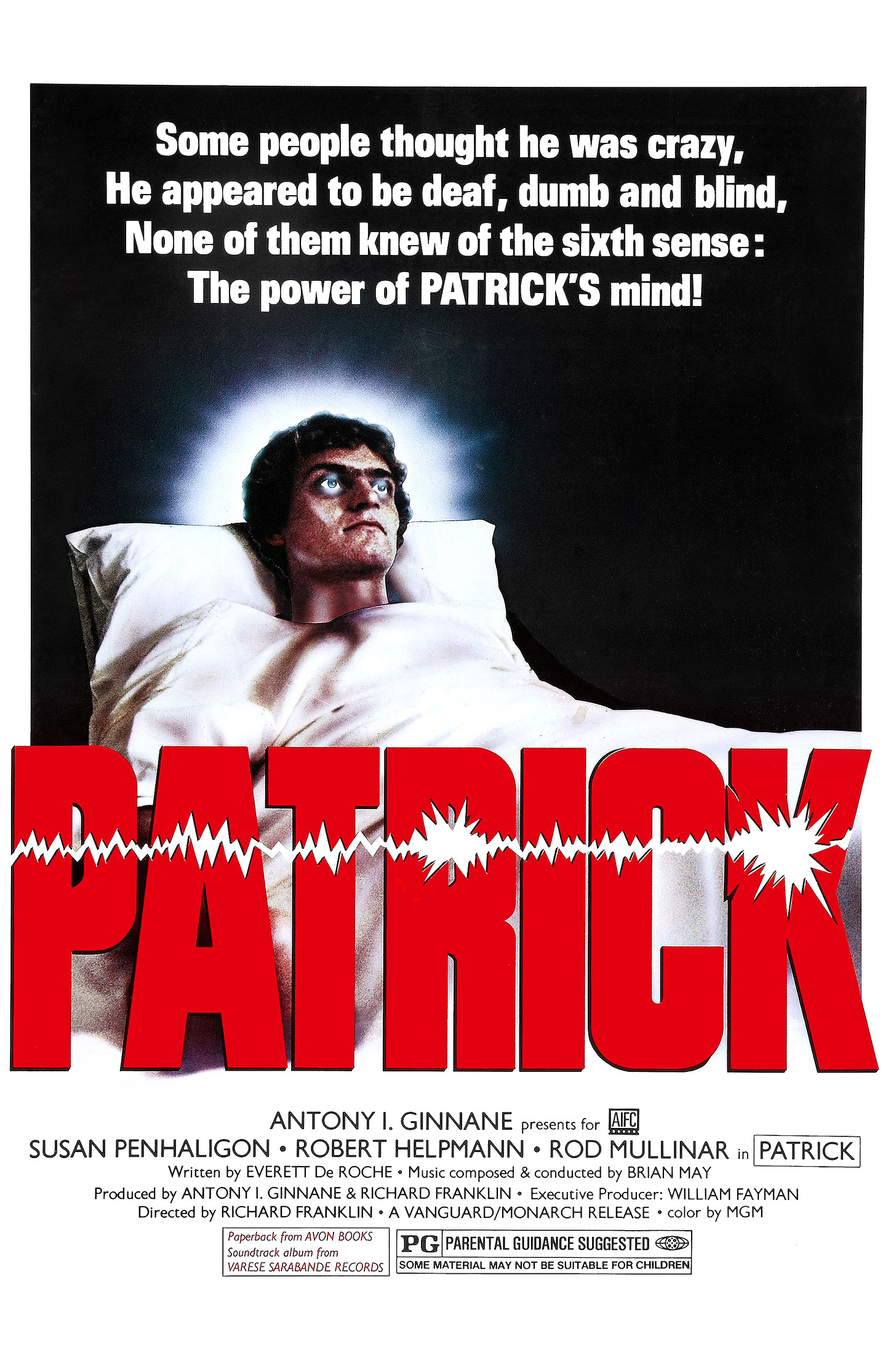

Patrick (dir. Richard Franklin, 1978)

Patrick is a horror film about a man who is kept alive in a comatose state after murdering his parents. Possessing psychokinetic powers and consumed by jealousy, Patrick (Robert Thompson) wreaks havoc on the life of the nurse he's become infatuated with (the British actress Susan Penhaligon).

It was the first collaboration between Richard Franklin and American screenwriter Everett De Roche, who also wrote the Franklin directed Road Games (1980), Link (1986) and Visitors (2003). Franklin was an Australian film student who attended the University of Southern California alongside George Lucas, John Carpenter and Robert Zemeckis. During his time there, he organised a seminar with Alfred Hitchcock in attendance after requesting permission to screen a retrospective of his work. Hitchcock would become a friend and major influence on Franklin's work, evident in the use of camera movement and framing in Patrick.

The pre-credit murder scene is a stylised set piece that resembles not only Hitchcock but also Brian De Palma, to many the natural heir to Hitchcock. Using split screen and action reflected in eyeballs and bedposts, it's clear from the start that this is a talented director at work. The sequence of events that follows also displays De Roche's skill as a writer, balancing the horror with some neat characterisation, while Franklin references Hitchcock further via Martin Balsam's doomed walk up the stairs in Psycho (1960).

Far better than your average exploitation horror, it comes with a good score by Australian composer Brian May, known for his work on the first two Mad Max films. In the Italian version, the music was redubbed by Dario Argento favourites Goblin.

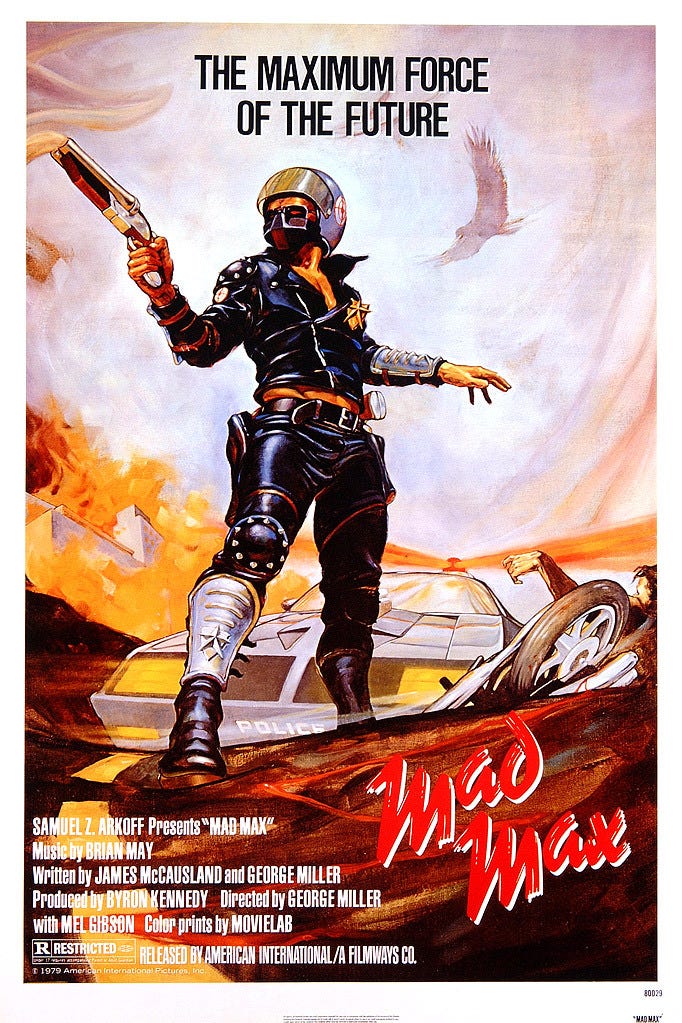

Mad Max (dir. George Miller, 1979)

The original, though not necessarily the best, film in the Mad Max series, George Miller's debut is still a raw, blistering masterpiece.

Most people will probably already know the story: Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson) lives two lives: that of a doting husband and father, and as a cop doing battle on the roads with a gang of deranged bikers.

Low angle tracking shots that obliterate the horizon, amazing stunts, kinetic action sequences, seamlessly edited together car chases, Hugh Keays-Byrne as the Toecutter, and all shot in widescreen anamorphic using a lens left over from Sam Peckinpah's 1972 flick The Getaway; all reasons to watch this film at least three times in your life.

Favourite shot: Dressed in black leather, Max walks away from the camera, fades away, and emerges out of the dark as a black suped-up Pursuit Special. Man and machine becoming one.

An absolute classic.

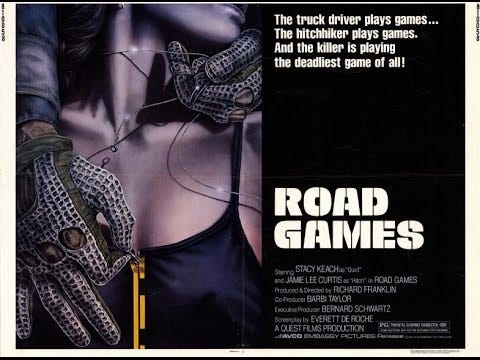

Roadgames (dir. Richard Franklin, 1980)

After working together on Patrick, director Richard Franklin and screenwriter Everett De Roche collaborated a second time on Roadgames, a psychological thriller starring Stacy Keach and Jamie Lee Curtis.

Already a fan and scholar of Alfred Hitchcock, Franklin had given De Roche a copy of the script to Rear Window (1954) as an example of how he could tighten up his own script for Patrick. After reading it, De Roche saw the potential in a similar story being transferred to the open road, combining elements of classic Hitchcock (the wrongly accused man, voyeurism) with Australian film's preference for vehicles and the open road (from The Cars That Ate Paris in 1974 to Mad Max 2 in 1981).

Keach plays Quid, a long haul truck driver who passes the time by ruminating on the lives of other drivers on the road. When he witnesses strange goings on at a motel, he begins to suspect a van driver of being a serial killer. Along with hitchhiker Pamela (Curtis), he decides to investigate.

Shooting in Panavision, Franklin utilises the screen to show how vulnerable Quid is; an American in a country whose residents do little to hide their dislike of him, the wide open spaces offer a potentiality where anything can happen largely unseen. Told entirely from Quid's point of view, De Roche asks the audience to put their faith in an unreliable narrator; Quid is sleep deprived throughout and hallucinates, particularly when driving at night.

Though it sags slightly in parts, this is a solid thriller. Keach (always an undervalued actor) has the likeable everyman quality of a James Stewart or Henry Fonda, and for Hitchcock fans there are some nice references (Quid gives Pamela the nickname Hitch, and a copy of a Hitchcock magazine is seen in the truck), and it ends with a blackly comic visual punchline that Hitchcock himself would have loved.

Overall, well worth a look, either as a double bill with Patrick or alongside other great killer on the road movies like Duel (1971), The Hitcher (1986), Breakdown (1997) or Joyride (2001).

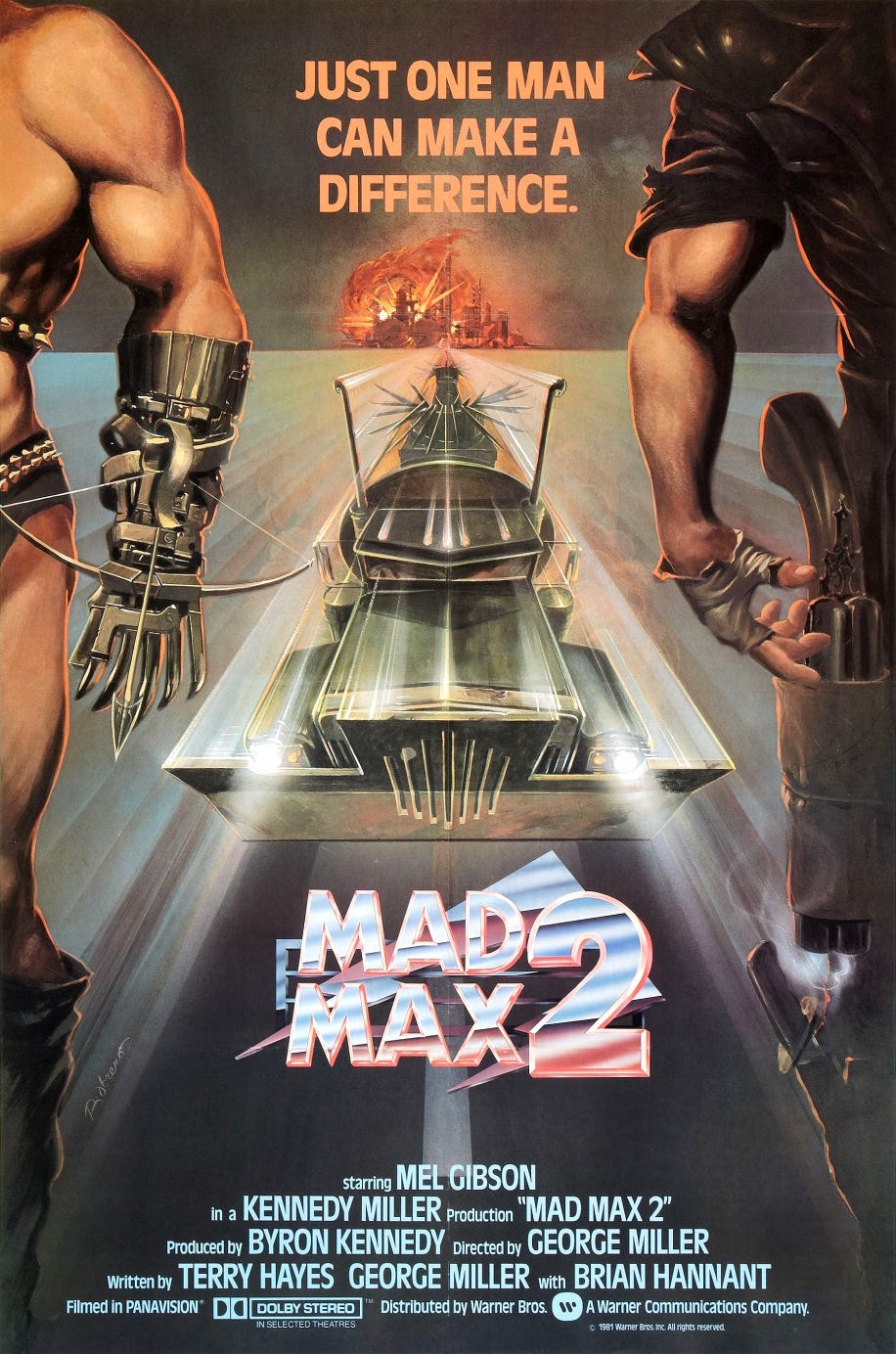

Mad Max 2, a.k.a. The Road Warrior (dir. George Miller, 1981)

In Mad Max 2 (released in America as The Road Warrior), Mel Gibson reprises his role as Max Rockatansky in one of those rare films, a sequel that surpasses the original.

The plot sees Max take on mythical hero status (Miller was influenced by Joseph Campbell's 1949 text The Hero With a Thousand Faces) when he comes to the aid of a band of settlers in return for the scarce gasoline that has become the lifeblood of a country surviving in the wake of a global war.

One of the most influential action films of all time, it's part science fiction and part frontier western (the feral kid in this film has the same look in his eye when he watches Max walk away as the kid in Shane (1953) did when he watched Alan Ladd ride out of town). It went on to spawn a host of sub-par post-apocalyptic sci-fi actioners and has been referenced in Weird Science (1985) and Raising Arizona (1987). It's also rightfully considered the best of the four Mad Max films, with 2015's excellent late addition Fury Road surprising everyone by giving it a close run for its money.

The film was heavily cut for its violence in both Australia and the States, and though a full uncut version no longer exists, the scenes of carnage and bloodshed are still as impactful now 40 years later. The climactic highway pursuit is breath-taking, eclipsing the truck chase in Raiders of the Lost Ark, also released the same year.

I remember watching this for the first time on VHS (probably in a crappily dubbed pan-and-scan version) and rewinding the last 20 minutes and rewatching it over and over. When it was released on DVD in all its widescreen glory, it was like watching it again afresh. And again this time around. And again the next time I watch it.

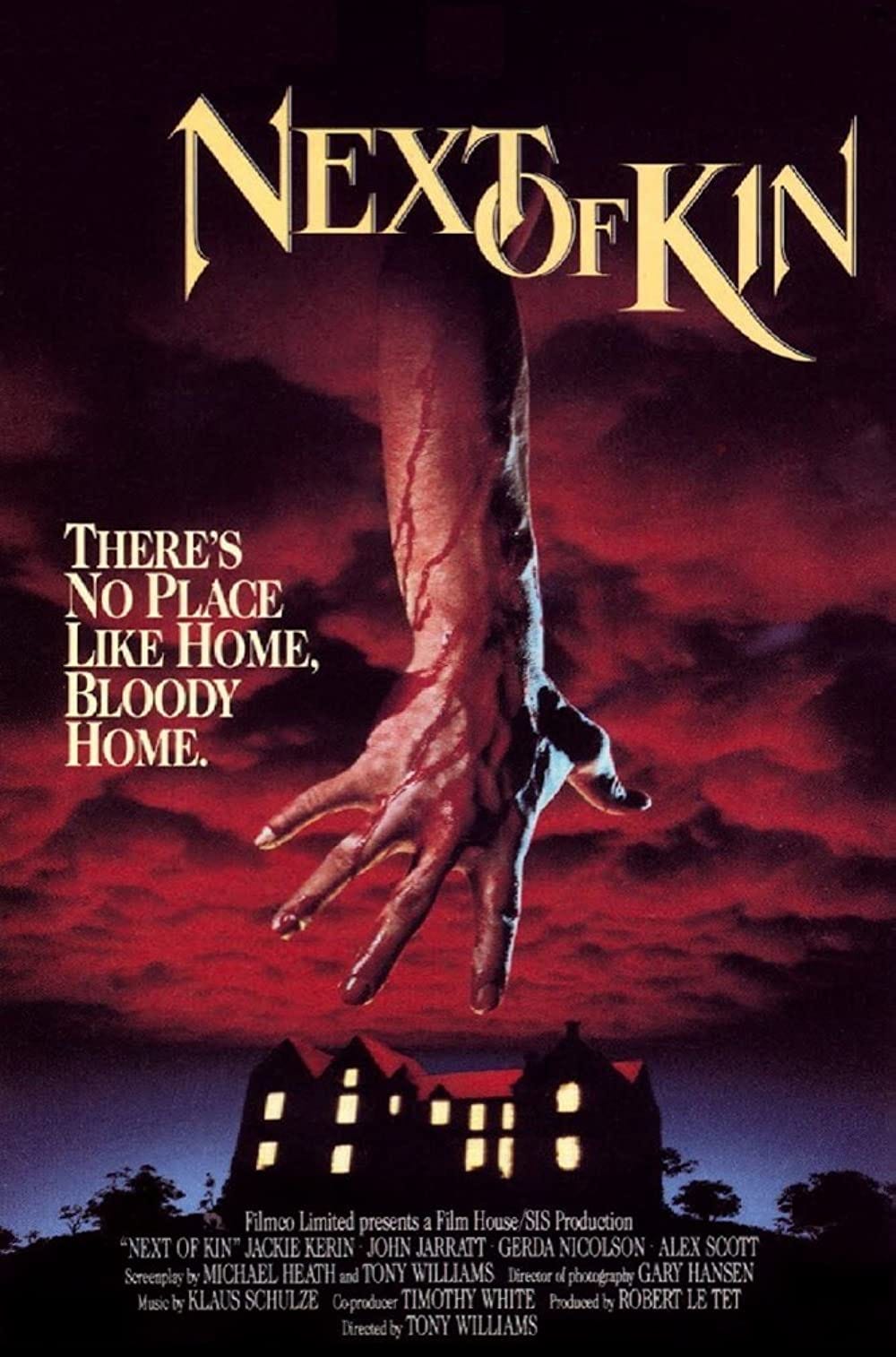

Next of Kin (dir. Tony Williams, 1982)

A criminally overlooked horror film with a great lead performance by Jackie Kerin as Linda, a young woman who inherits a retirement home for the elderly after her mother passes away.

The second of only two features directed by New Zealand documentary filmmaker Tony Williams, the film falls somewhere between Suspiria (1977) and The Shining (1980), and to be mentioned in the same breath as those two classics is testament to how good this film really is.

Essentially it's a haunted house film with a psychological horror twist, and Williams, cinematographer Gary Hansen, and co-scripter Michael Heath understand that the things you don't see are sometimes far scarier than those you do. The camerawork is phenomenal, the use of slow motion some of the best I've seen, and it has the scariest bathroom scenes since Psycho.

Favourite scene: Filmed in slow motion, Linda runs along a corridor and down a spiral staircase. To add to the terror, her scream is also slowed down to a guttural primal wail. Fantastic.

#

Also worth seeking out as a primer is Mark Hartley’s 2008 documentary, Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation!

These reviews were previously posted on my Instagram page @filmfolkuk