There is a passage in David Gaffney’s 2022 novel that brings to mind Norma Desmond, the faded movie star in Billy Wilder’s Hollywood noir Sunset Boulevard. Daniel Quinn, a twenty-six year old obsessed with Out of the Dark, a forgotten 1960s British B-picture, observes its washed-up star Mathilde Pelletier from a door in her West Midlands flat:

I went to get whiskey and when I returned she was standing motionless in the middle of the room, staring. It was as if she could see the ghosts of Hamish McGrath and Otto the director and the script girls and the best boy and the gaffer and the lighting men and sound men flitting about the room going about their work, imprinted into the fabric of the walls like a Victorian lantern show. She was hypnotised and I followed her gaze and after a time believed that I too could make out some faint shadows that might have been the spectral remnants of that powerful story.

Memory, duality, illusion and reality, the past and the present all merge throughout the book as Daniel becomes embroiled in a mystery that could have served as the plot for a classic noir.

A beautiful woman older than he, a child in need of help, and a man who insists on renting Daniel’s garage for what may be an altogether darker purpose than merely using it for storage, infiltrate Daniel’s life as he attempts to make sense of a mystery closer to home, and that is somehow entwined into the fabric of Out of the Dark’s frames.

With its action set in the West Midlands in the late 1980s, the story has the bleak neo-noir feel of Mike Hodges’ Get Carter by way of 1967’s The Whisperers and Ramsey Campbell’s unsettling urban horrors. Soundtracked by bands like Scritti Politti and Alien Sex Fiend, one can almost hear the mournful tones of Dead Can Dance’s ‘The Host of Seraphim’ echoing off the concrete as Daniel sits on his balcony and watches the traffic’s red and white blobs float along the M6’s motorway intersection; it’s visual imagery fitting for a screenplay but written in prose, and during moments like these, Gaffney’s deft touches skilfully blur the lines of what we take as reality and how Daniel sees the world around him.

As someone who has walked the streets of Manchester city centre at dusk as Marvin Gaye’s soundtrack to Trouble Man plays through his headphones, I was able to identify instantly with Daniel’s point of view. Film remains the most powerful artform of the twentieth century, and though we’re now living in an age of streaming services, the experience of leaving a cinema after watching an obscure film with a small number of strangers is still a potent memory. The need to bottle that feeling can dictate the way we walk, speak and act, as we consciously try to emulate what we’ve just seen. In Daniel, that wanting to be a part of a film is taken to its next logical step as he moves into a flat where he believes scenes from Out of the Dark were shot. When he discovers that the woman living in a neighbouring flat is Mathilde, he embraces the opportunity to get to know her, firstly as a fan, but then, as it becomes apparent that she is in need of him, as a character appearing in a film she’s magically stepped out of.

Switching between the plot of the film as Daniel searches for clues and pauses the action intermittently on a scratchy VHS copy, Gaffney resolutely brings the action to its natural conclusion in classic noir style. Daniel is all too willing to slide himself into the lives of the estate’s residents while he sees them as invading his own, culminating in a final act that reads like a pitch for the best film noir you’ve never seen. The shift from Daniel’s first person narrative to the third person as he observes himself undertaking tasks at Mathilde’s behest is masterfully structured, tying together two narratives that have been running in parallel with each other: that of the film and Daniel’s personal journey.

For all its allusions to noir, Out of the Dark isn’t just another thriller. Thematically, it bears a resemblance to Theodore Roszak’s bloated but interesting Flicker, while its tone is closer to Nicholas Royle’s Director’s Cut. Its mystery plot often takes a back seat to its explorations of grief and how we search for answers in the hope that we may eventually be released. There’s a definite purpose in Daniel’s rewatching of Out of the Dark that goes beyond his ambition to become a film theorist, while the decisions he makes when faced with the very real possibility of becoming a player in an actual mystery are borne of a need to escape reality; the irony, of course, being that his present situation is the reality, no matter how much he views it through a lens.

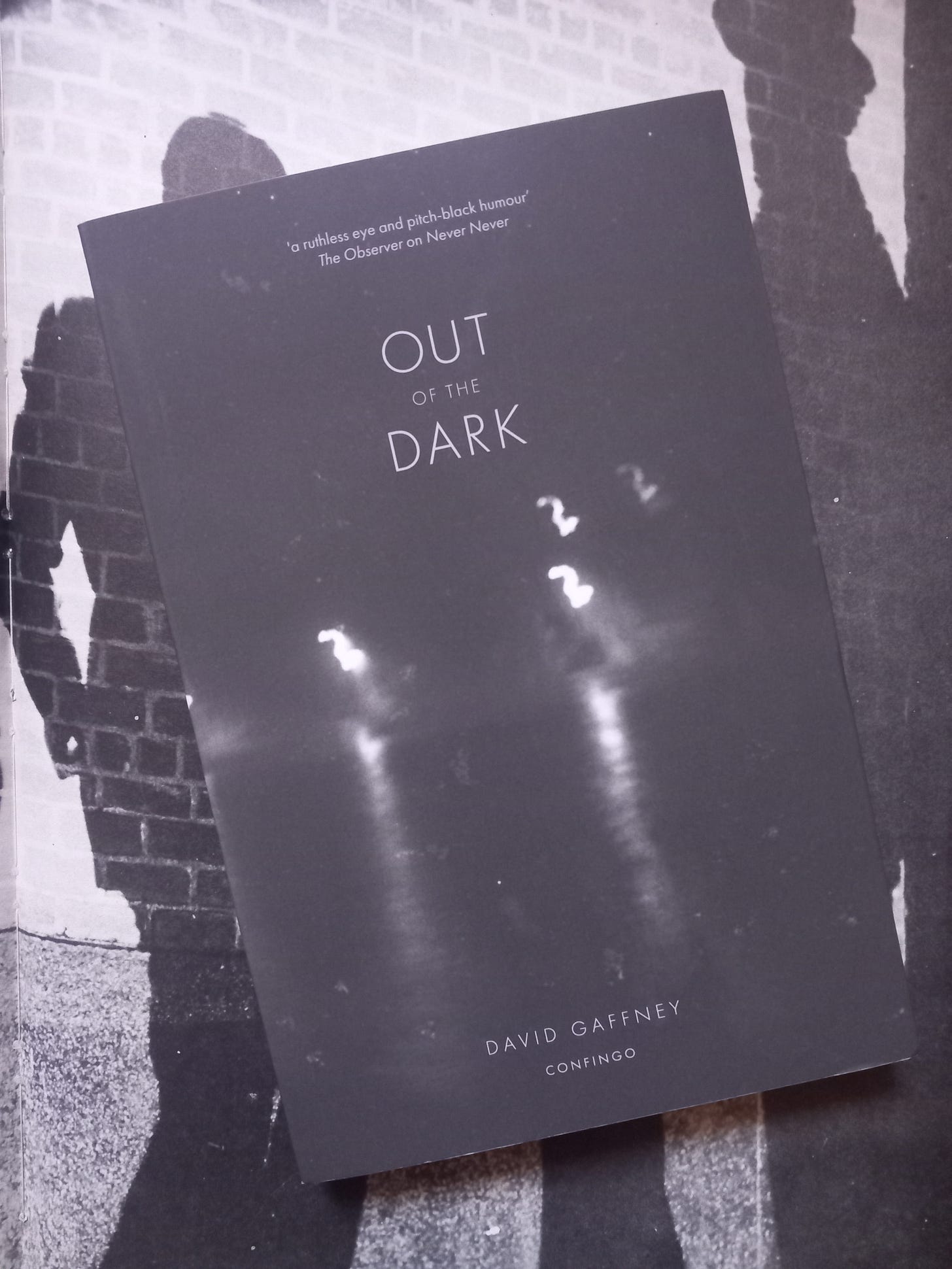

Out of the Dark can be ordered through Confingo Publishing.