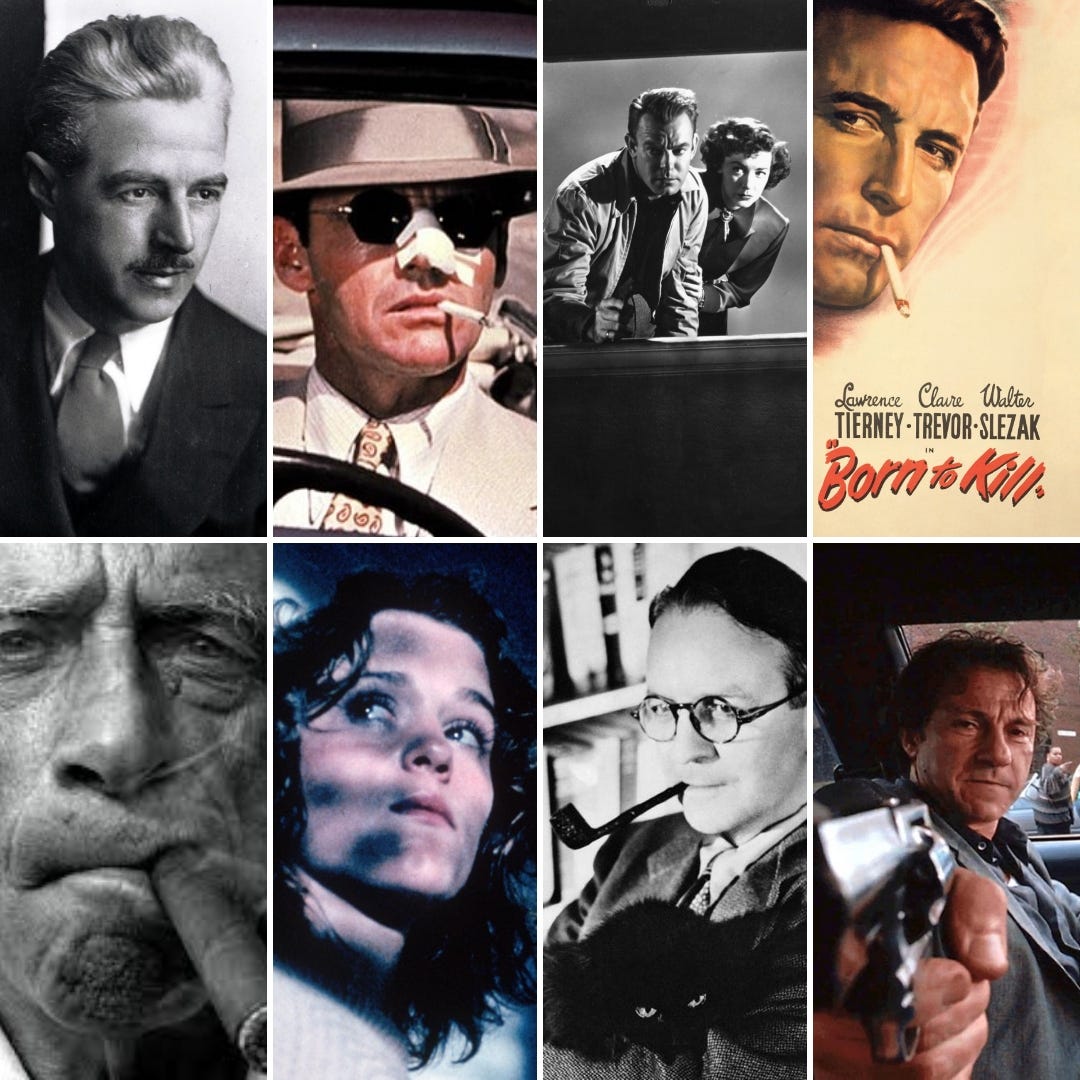

Clockwise from top left: Dashiell Hammett; Chinatown (1974); Raw Deal (1948); Born to Kill (1947); Bad Lieutenant (1992); Raymond Chandler; Blood Simple (1984); Samuel Fuller.

#

“Listen, kid,” he said. “If you going to jump on a bandwagon, you need to pick your jumping off point carefully.”

Noirvember, a celebration of film noir on Instagram, is my favourite band wagon. It encourages me to seek out more films, primarily B-movies, obscure neo-noirs, and the classics I either should have watched already, or enjoy revisiting. But I can’t just wade in blind. I need a jumping off point to guide me in before I go off on tangents inspired by other works referenced along the way. These encompass comic books, hard boiled crime novels and, of course, American movies dating from the 1940s up until Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil in 1958, considered to be film noir’s epitaph and after which a new term had to be invented: neo-noir.

The films that fall into this category are those produced during the 1960s up until the present, taking the form and playing around with it, with many succeeding tremendously. Notable neo-noirs include Point Blank, Taxi Driver, Thief, Drive, Chinatown, The Grifters, Blood Simple, and Bad Lieutenant. Other films, such as Francois Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player or Jean-Pierre Melville’s output from Bob le flambeur onward, pay homage to the American films in a uniquely French way. That the French coined the term, and, more importantly, laid the foundations of film noir through the Poetic Realism movement in the 1930s, it only seems right that their own crime pictures should be cut from the same cloth.

Then, a filmmaker will come along and muddy the waters, like Jean-Luc Godard did with his science fiction noir Alphaville in 1965. Later, Ridley Scott would pull the same trick by making his own science fiction film, Blade Runner, and dress it up in a trench coat. It was hugely influential, and gave rise to other sci-fi noir like Gattaca, Ghost in the Shell, Dark City, and Minority Report. Because all of these films are set in the future and explore the possibilities of technology and its impact on identity and the criminal landscape, another term was required: Tech Noir. Then, of course, Scandinavia had to have a go, and because their take on crime fiction is so bleak, as evidenced in the TV series The Bridge and The Killing, it would have been just plain ignorant and a little xenophobic not to welcome them into the noir club. Cue the ridiculous but apt label Snow Noir, whose roots can also be found in Jacques Tourneur’s Nightfall, a 1955 film noir that had a direct influence on the Coen Brothers’ neo-noir Fargo, while informing other films like Sam Raimi’s A Simple Plan and Taylor Sheridan’s Wind River, except the latter is referred to as a Western-noir, as is the Coens’ adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men. Why? Because the protagonists wear Stetsons. But it’s the style and mood of noir that counts, not the choice of headgear, so it’s best to view these works as mood pieces caught in a very far reaching net. Or better still, read Paul Schrader’s essay published in Film Comment in 1972, Notes on Film Noir, to get a full grasp on post-war film noir.

But to my jumping off point. I recently read Ed Brubaker’s twenty issue comic series Kill or be Killed, a review of which can be found elsewhere on my Substack, so I won’t go into it again. It was good to read something published as late as 2017 that carried on the noir tradition in comic book form. However, it was the essays in the back of each issue that set me off on a mission to watch every film recommended by critic Kim Morgan, who, incidentally, co-wrote the neo-noir remake of Nightmare Alley with husband and director Guillermo del Toro. The order in which the essays were published aligned with the action that had taken place in each subsequent chapter of Brubaker’s story. For example, the post-9/11 anxieties felt by the protagonist in the fourth issue were accompanied by Morgan’s essay on Little Murders, a film that dealt with post-JFK assassination anxieties felt by New Yorkers in the early 1970s. And so these essays ran, forming an arc that culminated in a 1951 film noir titled He Ran All the Way. I also watched a few films I selected myself: Chinatown, Bad Lieutenant and Blood Simple.

I began my journey sometime during the first week of November with Murder by Contract, a low-budget gem made in 1958 and starring Vince Edwards as Claude, a man prone to waxing philosophical as he takes on work as a hit man to help make down payments on a house. Lean, precise and a little bit strange, he's an enigma to his handlers, George and Marc (played by Herschel Bernardi and Phillip Pine), who are given the task of aiding him as he goes about the business of executing a witness in the prosecution of a mob boss. The problem for Claude is that the witness is a woman, and because women are unpredictable in his eyes, he has to come up with ways of killing her other than the usual methods he'd use on men. That might sound nuts, and it is, but because Claude is so sincere when he talks (and he talks a lot), you kind of agree with him without really understanding why. What's funny about the film is that George sees him as a genius, while Marc just thinks he's a pain in the ass for not just using a gun to get the job done. Instead, Claude invents absurd ways to execute a person, even toying with the idea of using anti-tank artillery before explaining why it wouldn't work and the hypocrisy of a system that allows men to use such weaponry and be rewarded for it, while he, on the other hand, would go to the chair for killing one measly person to earn some extra dough.

Shot in a semi-documentary fashion, the leaps of faith the script demands nevertheless gel with the realism, and the score by guitarist Perry Botkin (reminiscent of Anton Karas's theme for The Third Man (1949)) helps to keep everything off-kilter. A favourite of Martin Scorsese, you can see its influence on Taxi Driver (1976) in Claude's do-it-yourself workouts in his apartment. Highly recommended.

Next up was Pretty Poison (dir. Noel Black, 1968), a fine little crime picture based on Stephen Geller's 1966 novel She Let Him Continue, starring Anthony Perkins as Dennis Pitt, an institutionalised arsonist and habitual liar. Out on probation, he meets Sue Ann (Tuesday Weld), and leads her into believing he's a spy for the CIA on a mission to sabotage the chemical plant he works at. The roles suddenly reverse, however, when Sue Ann reveals her own pathological tendencies.

This was Perkins' first Hollywood role since Psycho in 1960, after appearing in a slew of European films to avoid being typecast. He's great in this, especially during the film's first half when he acts out his fantasies, adopting a Dragnet type clipped vernacular and mannerisms he seems to have learnt from watching too much TV. Tuesday Weld matches him as the darker flipside to the same coin. Her portrayal of Sue Ann as a starry-eyed nymphette who turns into the pretty poison of the title is seductive and scary. Like Dennis, she is living out her own fantasy, and you can imagine her watching Bonnie and Clyde the year before and getting off on the violence; in one scene she is sitting in a cinema, clearly enraptured by the gangster film up on the screen. Where Dennis throws himself into his role with the same gusto as a boy playing pretend, Sue Ann is more committed to the part she's chosen to play right up to the bitter end. At the start of the film, Dennis's probation officer (John Randolph) warns him that the world is very tough and real with no place for fantasies. By the end of the picture, his warning sounds like an alarm bell going off. I found this on YouTube. Check it out.

After Pretty Poison, I watched Little Murders (dir. Alan Arkin, 1971), a biting satire adapted by Jules Feiffer from his 1967 Broadway play. Elliott Gould stars as Arthur, an apatheist who claims to feel nothing in the way of love or aggression. After a stranger named Patsy Newquist (Marcia Rodd) saves him from a beating, she berates him for failing to reciprocate when his tormenters turn on her. A commanding woman who sees life as a hurdle that can be overcome through a steadfast refusal to be defeated, Patsy romances Arthur in an attempt to get him to feel something. Taking him by the hand, she leads him through a series of encounters that reconfirm his belief in the failure of institutions, extending mainly to family, religion and the police force.

Influenced by the twin assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Lee Harvey Oswald, Feiffer portrays New York as a city spun out of control, filling the residents with existential dread. The people Arthur encounters are either deeply neurotic or turn to philosophy in order to make sense of the world around them. Patsy's father fears homosexuality to such a degree that he suspects every man his daughter brings home to be gay, while it's clear that his own son, himself a mass of anxieties, is the real cause for his concern. Her mother, meanwhile, quotes comforting gift card phrases her own mother said to her as a way of solving life's problems. Arthur's parents, on the other hand, are hugely intellectual and devoid of any parental feelings towards their son whatsoever. It's a film rich in strong characterisation, and the cast (some of whom, Gould included, reprise their roles from the stage production) play their parts perfectly. But it's the two cameos from Donald Sutherland as a new age priest and director Alan Arkin as a detective on the verge of a nervous breakdown that get the most laughs. Sutherland especially threatens to steal the film from everyone.

This is such a New York movie, in that the city is as much a central character as it is in The French Connection (1971), The Warriors (1979) or Manhattan (1979), and like the people who inhabit it, it's sporadically funny, pushing buttons that will either tickle you or not, depending on your own outlook on life.

Though Little Murders can in no way be classified as film noir, it does have a noir sensibility. Here, the city is the antagonist, at once causing the horror while looking on indifferently from the seats on a subway car as Arthur stands covered in blood (a striking image not quickly forgotten). In Arthur, it also has the doomed protagonist, who knows that the only way to cope with the daily beatings is by disengaging completely. In a rare scene that plays without sound, we're allowed to see life from his point of view as he snaps people in Central Park through a camera lens, a scene that would later be touched upon, albeit from the perspective of a deaf man, in Sound of Metal almost fifty years later.

M (1951) is Joseph Losey’s solid remake of Fritz Lang's 1931 classic (considered to be one of the first film noirs), with David Wayne taking on the Peter Lorre role as a child murderer. Relocating the action from pre-war Germany to post-war America, the film loses the expressionist grime of Berlin in favour of a sun bleached downtown LA, shot by legendary noir cinematographer Ernest Laszlo. Released during the height of McCarthyism, the parallels between the scapegoating of a murderer and that of a Hollywood filmmaker are clear, and it's no surprise that Losey himself was one of many who was placed under investigation by the HUAC for displaying communist sympathies.

In many ways, it's a needless remake, but it's still worth a look for Wayne's performance, and as another film that condemns the witch hunts that had Hollywood in a stranglehold, it still packs a punch.

Stand out moment: a mother's anxious flight down a seemingly endless staircase as she goes in search of her lost child. Also, by having the killer play a flute instead of whistling a tune, one is reminded of that other mythical child slayer, the Pied Piper of Hamlyn.

For those who don’t know, Samuel Fuller was a filmmaker who was reviled by dumb critics who saw him as a hack, and praised by fellow filmmakers who saw him as an auteur. Here are three quotes that sum up Fuller the filmmaker:

Francois Truffaut: “Sam Fuller is not a beginner, he is a primitive; his mind is not rudimentary, it is rude; his films are not simplistic, they are simple, and it is this simplicity I most admire.”

Martin Scorsese: “It’s been said that if you don’t like the Rolling Stones, then you just don’t like rock and roll. By the same token, I think that if you don’t like the films of Sam Fuller, then you just don’t like cinema. Or at least you don’t understand it.”

Sam Fuller: “If a story doesn't give you a hard-on in the first couple of scenes, throw it in the goddamned garbage.”

Fuller started out as a copy boy before graduating to crime reporter by the age of seventeen. By his early twenties, he had chosen to live his life as a hobo, travelling across Depression era America in a boxcar before landing in Hollywood where he penned pulp novels and wrote scripts for Columbia and Republic Pictures for over a decade before writing and directing his first feature, I Shot Jesse James in 1949. He served in WWII, and saw action in major campaigns in Africa and Sicily, his wartime experiences coming to bear on his films, notably The Steel Helmet and Fixed Bayonets! in 1951, and The Big Red One in 1980. Of the twenty-four films he directed, my two favourites are the two pictures he made at Allied International, Shock Corridor (1963) and The Naked Kiss (1964).

Fuller's films are pulp heaven (from the screenplay for Shock Corridor: 'Her body is a symphony, her legs a rhapsody'), and here, Fuller is at his most sensationalist, combining his background as a crime reporter and his talent at spinning a riveting, socially aware yarn in a trashy, surreal trip based in a mental asylum.

Johnny (Peter Breck) is an ambitious journalist with his eyes on a Pulitzer. Seeing an opportunity to solve a murder that's been committed there, he uses his stripper girlfriend, Cathy (Constance Towers), to pose as his sister so that he can pretend to lust after her and be committed.

What an outline for a story! I can imagine Fuller banging out the script on a typewriter, chewing his cigar, and envisioning the film up on a wall. And what's so great about Shock Corridor isn't only the plot ripped from a pulpsmith's fertile imagination, it's how said pulpsmith comments on America through the various patients Johnny comes into contact with. There's the soldier who believes he's a Confederate General in the Civil War, but whose reality is that he's been branded a communist during the Korean war; Trent, the black man who has been so traumatised by racism that he masquerades as a Klansman; and the atomic scientist who has regressed to a childlike state in the wake of the horrors of the atomic bomb. Then there are the nymphomaniacs who devour Johnny zombie-like when he wanders into their room, and the obese roommate Pagliacchi who force feeds him chewing gum and sings opera.

There are frequently inventive moments in Shock Corridor, like the use of colour stock footage to show how the patients view their dreams and aspirations, or in the case of Johnny, his nightmares in a stunning scene when a thunderstorm lashes the corridor from the inside. The cast is excellent, especially Breck as Johnny, Towers as the suffering Cathy, and Hari Rhodes as Trent.

Up there with other Sam Fuller classics Pickup on South Street (1951), The Big Red One, and White Dog (1982), The Naked Kiss stars Constance Towers as Kelly, a prostitute trying to make a new start in a white picket fence town. There, she meets Griff (Anthony Eisley), a shady cop who plays a major part in shackling Kelly to her past. When she lands a job caring for handicapped children and meets Grant (Michael Dante), things start to finally go her way.

A daring film for its time, The Naked Kiss is unflinching in its portrayal of prostitution, and controversially, Fuller also broaches the subject of paedophilia in a significant plot twist that kicks the doors open for a gripping final reel.

Towers is magnificent in the lead, and for those with a keen eye, you can get pleasure from seeing Shock Corridor playing at the local cinema, and Kelly reading a copy of Fuller's 1944 pulp novel The Dark Page.

Swapping the smaller aspect ratio and black and white photography of film noir for a widescreen, brightly lit colour palette, Roman Polanski’s 1974 masterpiece Chinatown is a key film from a decade that stands shoulder to shoulder with the 1940s as the greatest era in American cinema. Everything about this film is perfect: Robert Towne's script, Jack Nicholson's performance as private eye J.J. Gittes, Faye Dunaway as Evelyn Muwlray, the sumptuous production design and cinematography, Jerry Goldmith's score, and John Huston as Noah Cross, the personification of all that is obscene about wealth and greed. The terrible and bleak ending says as much about Polanski's return to Los Angeles in the wake of the Tate-LaBianca murders as it does about the climate in America after the disillusionment felt by the peace and love generation. Film rarely gets better than this.

Best line of dialogue: "I goddamn near lost my nose. And I like it. I like breathing through it. And I still think you're hiding something."

Next up was Born to Kill (dir. Robert Wise, 1947), a nasty, violent, excessive film, and because of all these things, it's top tier noir, with a cast of superb actors playing reprehensible characters, and clearly loving every minute of it.

Lawrence Tierney leads the pack as the psychotic Sam, a killer and opportunist who marries Georgia (Audrey Long), the sweet and innocent foster sister of self centred socialite Helen (Claire Trevor), a woman so morally corrupt, she carries on an affair with Sam while keeping her fiancé on side because both come with the promise of money, ill gotten or otherwise. Even the usually meek and put-upon Elisha Cook Jr., who plays Sam's friend Marty, isn't adverse to knifing an old lush (Esther Howard, great) to death when she threatens to blab to a private eye (Walter Slezak, also great).

This was Robert Wise's first film noir after he worked with Val Lewton on a run of exceptional horror films for RKO, and it was met with so much controversy that the studio immediately distanced itself from the film. At the time, Tierney was making headlines through a series of drunken brawls offscreen, and matched with the violence his character dishes out on screen (starting with the double murder of his girlfriend and her one night stand), it all got a bit too much for the MPAA, who increased restrictions on violent films. It was banned in three states and became the focal point of a court hearing after the killing of a 7-year-old boy at the hands of a 12-year-old who'd watched the film prior to the murder. Like a lot of films that have been connected to real life violence, it suffered a huge backlash from critics, which is a damn shame because it has a believable and exciting script, intense performances from Tierney and Trevor, and taut direction from Wise.

Yet another first time watch for me, and a satisfyingly unpleasant discovery it is. Check it out as soon as possible.

Mikey and Nicky (dir. Elaine May, 1976) is a talky character study about two mobsters, Mikey (Peter Faulk) and Nicky (John Cassavetes), and how their already taut friendship is tested after Nicky steals a thousand dollars from their boss.

Shot on the streets of New York City, the action takes place over a few hours, starting at around 10pm and ending at daybreak. It has the same feel as Martin Scorsese's Mean Streets (1973), with shots at times pulling out of focus and the rain and neon blurring the backgrounds. Mikey and Nicky are similar to Charlie and Johnny Boy too; Nicky especially has the same volatile edge that made Johnny Boy such a dangerous presence whenever he was on screen. Mickey, like Charlie, is the more level-headed of the two, looking out for his friend while at the same time trying to keep on side with his boss. We follow them as they ride buses (look out for M. Emmet Walsh as a driver), haunt bars, break into a cemetery to visit Nicky's mother's grave, and walk the streets, biding time until the inevitable denouement.

At first, you'll like Nicky for the same reasons Mikey does. He's funny, charming, and makes life interesting. But as the film progresses, you begin to see him for who he is: a bully who uses Mickey and women whenever he needs help. Mickey is no angel and is equally prone to outbursts of violence and abuse, but unlike his friend, his frustrations at being overlooked and disrespected are what drive his darker urges. Nicky, on the other hand, uses his charisma and repetitive questioning to force people into submitting to his whim until all that's left is him.

Falk and Cassavetes were close friends, and writer-director Elaine May gives them time to display their natural chemistry with one another as they run off with their mouths, laugh and fight, while cinematographer Victor J. Kemper (who also shot The Friends of Eddie Coyle and Dog Day Afternoon), closes in tight on his subjects as a gun for hire, played by Ned Beatty, pursues them across town. It's a pretty great film all round, and the two leads are magnificent.

Who Killed Teddy Bear? (dir. Joseph Cates, 1965) is a neo-noir sexploitation (pick your sub-genre and have fun with it) movie starring Sal Mineo and Juliet Prowse in a tawdry tale of voyeurism, fetishism, rape, pornography and, of course, murder (not forgetting the subtle hints of masturbation, lesbianism and incest). Vastly underappreciated, the film's influence can be seen on later sleazoid classics like Taxi Driver (1976) and Tightrope (1984), especially on the latter in the character of Lieutenant Dave Madden (Jan Murray), a widowed cop who takes his work home with him and paws over taped confessions of sexually abused women while his daughter listens in from the next room. This is the most interesting aspect of the film: a cop exposes his ten-year-old kid to the dangers of the world, while a psychopath shields his adult but mentally deficient sister from the same.

The groovy soundtrack is of its time and just a bit on the naff side, but the NYC location photography is stellar. It's also a painful reminder of Sal Mineo's enormous talent as an actor, going from vulnerable and pathetic to domineering and hateful in the blink of an eye.

Always undervalued as a director of film noir (perhaps due to the humour he injects into his suspense films), Alfred Hitchcock nevertheless made a bona fide noir with The Wrong Man in 1956. Released the same year as Hitchcock's remake of his own film, The Man Who Knew Too Much, which featured Doris Day singing "Que Sera, Sera," The Wrong Man is a sombre affair more in keeping with I Confess (1953) than the other dark but entertaining thrillers Hitchcock stormed the 1950s with. It also pointed to the darker direction he'd go into with his next film, Vertigo, in 1958.

Surprisingly, this was the only film Hitch made with Henry Fonda, as the casting of the actor, the very figure of integrity, as a wrongfully accused man is perfect. Based on a true story, it has an almost documentary feel in its attention to the technicalities of the justice system from the policework to the courtroom, but it's also incredibly stylised and very much a Hitchcock movie, with its preoccupation with Catholic guilt and the wrong man story that was the backbone of The Thirty Nine Steps (1935), Young and Innocent (1937), North by Northwest (1959) and Frenzy (1972), informing his work here.

At times deceptively simple, it's a film that requires closer inspection to appreciate Hitchcock's genius. The way in which Christopher Balestrero (Fonda) and his mentally unstable wife Rose (Vera Miles) physically separate from each other in the frame as Balestrero's guilt comes into question, the darker tones as they seek in vain to talk to possible alibis, and the constant sound of trains passing them by as they remain locked in a financial and unjust nightmare. And the greatest moment, Balestrero silently praying to a picture of Christ as his face dissolves into that of the real culprit, who is then apprehended. We're led to believe that prayer can produce miracles until Balestrero visits Rose in hospital to share the good news, only to find his wife as lost to him as before. Like us, he too was expecting another miracle.

Next up, I turned to the Coen Brothers, in my opinion the greatest screenwriters to grace the cinematic landscape since their debut Blood Simple in 1984. I always find their crime pictures to be the most satisfying in this respect, whether they’re paying their dues to Hammett in Miller’s Crossing (1990) or Chandler in The Big Lebowski (1998), or just making a straight up homage like The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) or giving us something uniquely fresh and exciting as Fargo (1996).

Blood Simple a stunning debut that builds its labyrinthine plot through a series of What if? scenarios. What if a husband paid a private eye to find proof of his wife's infidelity, then hired the same P.I. to kill both her and her lover? Then what if the P.I. killed the husband with the wife's gun, and the lover who we thought was dead turned up and tried to dispose of the husband's body in case he got blamed for it? But then what if the husband wasn't dead after all, and the lover suspected the wife of trying to murder her husband? In less capable hands, this would be farce (something the Coens can be guilty of), but in Blood Simple, every twist feels like a natural progression, right up until the end when the P.I. finds himself on one side of a wall with his hand pinned to the windowsill on the opposite side.

The wide and flat Texas landscape makes it possible for crimes to go unnoticed by the law, while its perpetrators murder, plot and bury alive under the cloak of a neon blue nightfall. When they are exposed in the flash of lightning or beneath the glare of a naked bulb, they are left wide open to being found out or the threat of a gunman picking them off through a window.

By far one of the best neo-noirs of the 1980s, it would take the Coens 23 years and No Country for Old Men to make a film as bleak as this again.

Too Late for Tears a.k.a. Prison Bait (dir. Byron Haskin, 1949) is a film noir with a "money is the root of all evil" message that features one of the most memorable femme fatales in Jane Palmer (Lizabeth Scott), a woman so determined to elevate herself above her middle-class social status that she'll kill, kill and kill again in order to get her hands on whatever amount of money she can. So, when a bag holding $60,000 literally lands in her car, it can only spell doom for every man who tries to keep it from her. This includes her husband Alan, played by Arthur Kennedy as a man so honest to goodness he wants to hand the money in to the police, while Dan Duryea plays Danny, a far more interesting and complex character who turns up on the scene to claim the money for himself. Watching Danny go from a female slapping thug to snivelling patsy as he gets further out of his depth is the film's main attraction, and Scott is clearly relishing her part as a woman who steadily takes him apart.

The script by Roy Huggins (creator of The Fugitive and The Rockford Files) throws the amount of curve balls one expects from this type of film (see other stolen money cautionary tales like Shallow Grave (1994) and A Simple Plan (1998)) but fails to build on the background story that could have explained Jane's obsession with climbing the social ladder.

Strangely, this slipped under the radar for a long while and only began to gain recognition after it was unearthed and restored in 2014. I'm glad it did because it's a very good, tightly scripted film with wonderful performances from Scott, Duryea, and Don Defore as the charismatic spanner in Jane's works.

He Ran All the Way (dir. John Berry, 1951) is a home invasion film starring John Garfield as Nick, a wanted man holed up in the home of the upstanding Dobbs family. Daughter Peggy (Shelley Winters) goes gooey eyed over their captor while her dad (Wallace Ford) looks on in horror. The two scenes featuring Gladys George as Nick's mother from hell are brilliantly played but too brief inclusions that reveal enough about Nick's character to make you feel almost sorry for him. There's a well staged and tense scene at the Dobbs' dinner table that highlights Nick's inability to converse with regular folk, not helped by the fact that he's brandishing a gun while being baffled as to why they won't eat with him.

Another good film tarnished by the shadow of McCarthyism, it was co-written by Dalton Trumbo while he was imprisoned, and it would be Garfield's last film before his premature death at 39 from a heart condition worsened by the blacklist.

The controversy caused by the release of Bad Lieutenant over thirty years ago cannot be overstated. Both the censors and the moral right were up in arms about Abel Ferrara's unflinchingly honest portrayal of an unnamed New York City cop (Harvey Keitel) whose addictions to alcohol, drugs, gambling and vice lead him tumbling headlong into the maelstrom. The two scenes that caused the most uproar were the rape of a nun and the how-to long take of the lieutenant shooting heroin. The rape scene is especially problematic. It's the only scene in the entire film that doesn't feature Keitel, and because of this, it is highly unnecessary. The lieutenant peering through a crack in the door and listening to the doctor's litany of the nun's injuries post-rape is more shocking, clinical and degrading, and thus far more impactful in its detachment. The rape itself is shot, edited and lit in a way that smacks of exploitation. It cheapens what is otherwise one of the best films of the 1990s.

My favourite scene in Bad Lieutenant comes at the very start of the film. The lieutenant drives his two sons (they look around 12 years old) to school. On the way the kids bicker, fool around and cause a commotion in the way kids too. Their dad berates them for being too loud and boisterous, and they quieten down. They don't get upset or answer back. Instead, a knowing glance passes between them. They've become used to their dad's outbursts. His morning moods are just a part of his personality, and the fact that one son kisses him goodbye shows that they don't feel threatened by him. As soon as they're out of the car, the lieutenant, not appearing to care who sees him, takes a few hits of coke and begins his day.

For the 35 minutes that come after, we follow him as he takes stolen money from two stick up men, smokes crack in a stairwell, sexually abuses two teenage sisters who are caught driving without a license, and makes increasingly risky bets on the World Series through a bookie with ties to the mob. He drinks constantly from a bottle of vodka and crashes out wherever his drug addled body and mind collapse, whether in seedy pads or on the couch in his family living room. During it all, his wife, mother in law, children, dealers, fellow cops, and perps step aside and let him pass through their lives. He abuses himself and his authority, and they allow it (and sometimes enable it) because he's gone beyond the point of ever being saved.

What makes Ferrara such a skilled filmmaker is that he makes us become invested in the plight of an irredeemable soul, and what's more, he plunges us into the lieutenant's lifestyle before we've had a chance to even try to get a handle on who this man is. We're carried along from one atrocity to the next until the corruption becomes palpable, and it takes the worst atrocity of all, the rape, to offer the hope of redemption as something to hold onto.

If the MPAA were braver, they would have given Keitel an Oscar for this (I'm not sure he was even nominated). He literally lays himself bare, exposing his character's soul for all to see. I can't think of any other performance by an actor that comes anywhere close to the intensity he brings to the role. The lieutenant should be, and for the most part is, the most reprehensible character in film history, but Keitel instils in him a certain something through a look or mannerism that shows us he might be worth rooting for.

Not an easy watch (as if it needs stating), but it is an essential one if you can appreciate it for its sheer raw energy. They still should have left the rape on the cutting room floor though.

I couldn’t have picked a better film to round off my noir binge than Raw Deal (dir. Anthony Mann, 1948), a five star film noir starring Dennis O'Keefe as Joe, a fall guy owed $50,000 for doing jail time for mob boss Rick (Raymond Burr). To avoid paying Joe, Rick engineers an escape that's sure to fail. But with the help of his girlfriend Pat (Claire Trevor) and case worker Ann (Marsha Hunt), Joe manages to overcome the odds stacked against him and sets off on a trail of destruction that ends in fire and bloody revenge. To complicate matters, a love triangle develops along the way between Joe, Pat and Ann, festering jealousy, betrayal and murder.

Outstanding in every way, the performances by the three leads are excellent, and I especially liked the standard noir voice-over narration being spoken by a female for a change. The characterisation is rich, the running time goes by in a flash, and the action doesn't let up for a second. The cinematography by John Alton is second to none; the scenes that take place in woodland and the countryside are the closest you'll get to a crossover noir western and point towards the direction Anthony Mann would go in with his dark westerns in the 1950s. Violent for its time, it features the most brutal out-of-the-blue assault on a woman since James Cagney's grapefruit tantrum in The Public Enemy (1931) while anticipating the notorious boiling coffee nastiness of The Big Heat five years later.

All in all, pretty damn flawless.

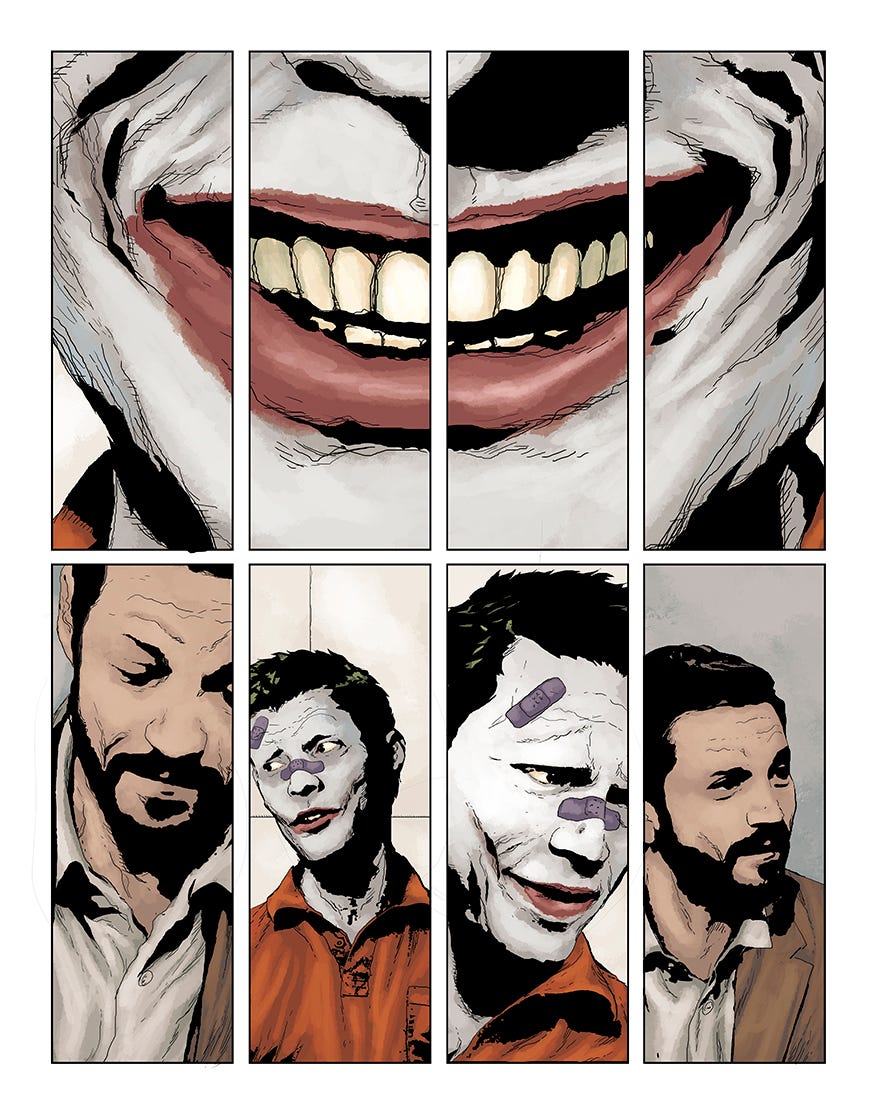

In between films, I’ve got to read, and Joker: Killer Smile and the one-shot epilogue Batman: The Smile Killer by Jeff Lemire and Andrea Sorrentino landed in my lap at exactly the right moment. The best Batman stories have always been those that adhere to the rules of noir, from Frank Miller’s Year One to Jeph Loeb and Tim Sales’ The Long Halloween and Dark Victory, and these four issues do just that, while encompassing everything I love about the Batman-Joker dichotomy.

Killer Smile is a Joker story told from the point of view of his psychoanalyst Dr. Ben Arnell, a father and husband who has taken on the unenviable task of trying to crack the Joker’s mind. Arnell is The Silence of the Lambs’ Clarice Starling to the Joker’s Hannibal Lecter, a career professional who believes rationality and perseverance will result in him being able to deliver a report that finally explains the Joker’s actions and, in turn, help to bolster his own profile. How wrong can one man be?

Over three issues, we witness Arnell’s mind succumb to the Joker’s influence, his family become threatened, and his eventual demise. It’s a dark, claustrophobic trip, but at least it comes with the promise of Arnell being avenged by Batman in The Smile Killer. How wrong can one reader be? If anything, the coda is worse than what came before, calling into question everything we thought we knew about the Batman, and in true noir style, colouring everything in greys.

Another exploration of the psychotic criminal mind, but this time told from the perspective of the psychopath, is Joyce Carol Oates’ 1974 novel Triumph of the Spider Monkey. Out of print for forty years, it was reissued by the good people at the incomparable Hard Case Crime imprint in 2019, with an accompanying novella titled Love, Careless Love.

Best absorbed in one sitting (it’s a lean 134 pages), Triumph of the Spider Monkey is a difficult read. Often, what is imagined and what is remembered is muddled. The unreliable narrator, after all, is a psychotic who murders women with a machete, but he’s also a guitarist who travels to Hollywood to make his name as an actor or musician or both (shades of Charles Manson immediately spring to mind).

The book is a bold attempt by Oates at trying to emulate the voice of a killer, and on the whole, she succeeds. The problem is, she succeeds too well, and the result is a confusion of hallucinatory imagery, medical reports, and court transcripts, all of which are filtered through a fractured mind, and just as you’re settling in to the rhythm of the prose, it ends. I was hoping the novella, told from another perspective, would have been more coherent and shed some light on the novel, but that too was difficult to dissect. As an experiment, it’s admirable. As the piece of crime fiction I was hoping for, it pales in comparison to other novels that have trod the same path, namely The Killer Inside Me by Jim Thompson, American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis, or the criminally overlooked Pharricide by Vincent de Swarte.

I managed to squeeze in other noir reading too this month. Killer in the Rain collects a selection of Raymond Chandler’s short stories, some of which he expanded for The Big Sleep and Lady in the Lake. Chandler was undeniably one of the great prose writers, but having read the novels, these stories served more as curios for me. Even so, he still knocks spots off most other crime writers out there. Hammett by Joe Gores is a novel published in 1975 that imagines the father of hard-boiled detective fiction Dashiell Hammett as a man forced to step back into his gumshoes after his friend is murdered. It’s a cool idea for a story. Hammett worked for the Pinkerton Detective Agency before becoming a writer, and Gores sets his story during the time Hammett was finessing his writing style with the stories he had published in Black Mask magazine while working on Red Harvest. Written in the style of Hammett without feeling gimmicky, Gores’ sense of time and place (San Francisco in the 1930s) is authentically realised through some wonderful slang-driven dialogue and a genuine feeling for the plight of the private investigator; not surprising as Gores himself worked as a P.I. in San Francisco for twelve years.

Whetting my appetite for San Francisco set tales, I picked up a copy of San Francisco Noir, a fine collection of contemporary noir from a host of writers exploring the worlds of communists, hookers, criminals and the type of characters who tread the line between right and wrong. Grab a copy if you can. The grey areas are always more interesting than those coloured in black and white.

So, November’s almost at an end, and I can already feel my tastes leaning towards the gothic in both film, crime and horror fiction. Hitchcock’s American debut Rebecca (1940) or Charles Vidors’ Ladies in Retirement (1941) should form a neat segue. On the reading front, Robert Aickman’s short stories are already proving to be a strange bedside companion for these darker months, as I’m sure the three Ramsey Campbell books (a novel, a novella, and a short story collection) that are casting shadows on my bedroom wall will too.