Nigel Kneale

An appreciation of the creator behind Bernard Quatermass and two of the creepiest television plays of the 1970s.

Born in England to Manx parents but spending his formative years in Douglas on the Isle of Man, Thomas Nigel Kneale has been commemorated this year with a series of six postage stamps that reveal hidden messages when placed under a UV light. They’re a fitting tribute to a writer whose love of English and Manx folklore, and that which is buried beneath the soil, informed his work, laying a bedrock for him to build his tales upon. In Britain, Kneale was to film and television what John Wyndham was to literature: a writer of incredible vision whose love of science fiction, horror and the occult helped fill a homegrown need in the British imagination that would have usually been satisfied by American masters of the genre like Ray Bradbury, Rod Serling, Jack Arnold, Richard Matheson or Harlan Ellison. While there is no intergalactic problem that can’t be solved in Wyndham’s work over a cup of tea and the deployment of some high explosives, in Kneale’s work, especially the haunting Murrain (1975), the problems aren’t so easily identified or disposed of. The ‘pattern beneath the plough,’ the very thing that lies beneath the earth and could, at any point and without warning, resurface is a theme that runs throughout his work, from the dormant aliens in Quatermass and the Pit (1957/1967) to the entity in The Stone Tape (1972) or the ages old suspicions that come to the fore in the aforementioned Murrain.

During a career that began with him displaying a talent for acting, Kneale soon concentrated solely on his writing after achieving some success with the publication of his short story collection, Tomato Cain and Other Stories in 1949. Going against his publisher’s advice to write a novel, Kneale chose to write for television and was employed as a staff writer at the BBC from 1951 where he turned his hand to writing dialogue, radio plays and children’s programmes. But it wasn’t until the six-part television serial The Quatermass Experiment was broadcast in 1953 that Kneale established himself early as a writer of unique vision.

Now that we have unlimited options to stream entire TV series at any given time of the day, it’s hard to imagine just how important a weekly serial was. The designated time slot put a stop to anything else that may have been planned, making each episode an event. The Quatermass Experiment, which went on to attract an unprecedented 3 million viewers and climbing to 5 million by the final episode, was the first of its kind: a science fiction TV series specifically aimed at an adult audience. When Hammer Studios remade the series as a film under the title The Quatermass Xperiment (the ‘X’ a celebration of the X-certificate it was awarded by the BBFC), Kneale’s work suddenly reached an even wider audience at both home and abroad in the USA.

In the wake of the Quatermass success, Kneale continued to write for the BBC, adapting both Wuthering Heights and Nineteen Eighty-Four before returning to the science-fiction and horror genres with his original script for The Creature, an abominable snowman tale that was broadcast in January 1955. Soon after this, the BBC commissioned Kneale to write a sequel to The Quatermass Experiment, and the imaginatively titled Quatermass 2 eventually went on to attract three times the amount of viewers during its six-part run as its predecessor. Again, Hammer saw a lucrative series that could easily be truncated into a feature length film and immediately hired Kneale to write the screenplay after his contract at the BBC expired in 1956. Quatermass II, released in the USA as Enemy from Space, was released in 1957, just three months before Kneale adapted his play The Creature as The Abominable Snowman for the big screen, again produced by Hammer. For the remainder of the 1960s, Kneale continued to write for both film and television, proving himself adept at bringing John Osborne’s plays Look Back in Anger and The Entertainer to cinema screens, whilst adapting Nora Lofts’ novel The Devil’s Own as The Witches for Hammer in 1966. His crowning achievement though, would be another six-part serial, Quatermass and the Pit, broadcast over the winter of 1958/59 and later adapted by himself for Hammer in 1967. During this period, Kneale wrote both adaptations and original plays for the BBC; some of these didn’t make it past the script stage (Brave New World, Lord of the Flies, and a controversial play titled The Big Giggle that dealt with teenage suicide), whilst others, The Year of the Sex Olympics (an ahead of its time play that predicted the reality TV shows that came to prominence in the new millennium) and The Stone Tape brought him further acclaim from both critics and audiences when they were broadcast in 1968 and 1972, respectively. Following the success of The Stone Tape, Kneale began working for ITV, writing the play Murrain and the six-part series Beasts before returning briefly to Quatermass with a four-part serial titled The Quatermass Conclusion (released as a feature length film for the overseas market) and a subsequent novelisation simply titled Quatermass.

Kneale’s only return to cinema came in 1982 with Halloween III: Season of the Witch, produced by John Carpenter, with whom he shared a brief connection. Asked by John Landis to write a script for a remake of The Creature from the Black Lagoon, a project that never materialised despite Carpenter expressing his interest in developing the project (he would instead remake The Invisible Man as Memoirs of an Invisible Man in 1992), Kneale then went on to script the third instalment in the Halloween franchise on the understanding that he could divert from the first two films; a decision endorsed by Carpenter who envisioned the franchise as a series of individual stand-alone pictures rather than retaining the focus solely on Halloween’s bogeyman, Michael Myers. When the backers demanded more graphic violence, however, Kneale asked for his name to be removed from the credits. He would return to writing for television again, this time adapting Susan Hill’s novel The Woman in Black for ITV in 1989. In the meantime, Carpenter would pay homage to Kneale by using the pseudonym Alan Quatermass when he wrote the distinctly Kneale-like Prince of Darkness in 1987.

Up until his death in 2006, Kneale wrote episodes for the TV series Sharpe and Kavanagh QC, and acted as a consultant on the live digital broadcast of The Quatermass Experiment remake for the BBC in 2005. That a man of his age was approached to write for The X Files (an offer he turned down) is testament to how much he continued to be revered by both his peers and contemporary writers of science fiction and horror, leaving his mark on writers and filmmakers of renown such as Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison, Guillermo del Toro and Kim Newman.

Below are eight of Kneale’s films and plays that display how imaginative, socially aware and ahead of his time his work was.

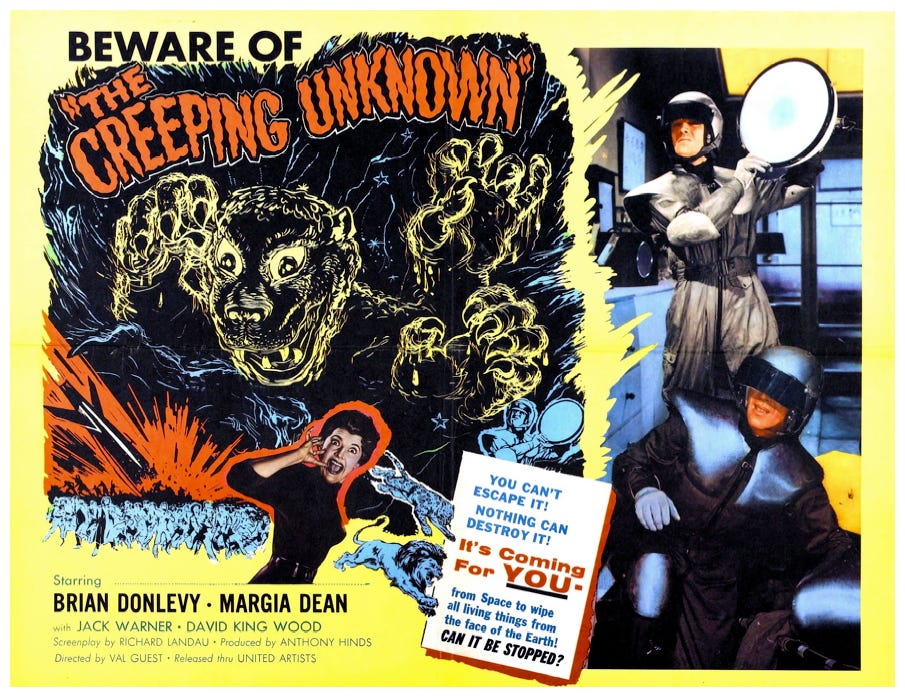

The Quatermass Experiment/The Quatermass Xperiment, a.k.a. The Creeping Unknown (1953/1955)

With The Quatermass Experiment, one is faced with three options to view: the original 1953 series (though frustratingly only the first two pre-recorded episodes have survived as episodes 3-6 were filmed live and are now considered lost); the live 2005 remake that marked a resurgence in science fiction on the BBC alongside the Doctor Who reboot; or Hammer Studio’s 1955 film version The Quatermass Xpriment (released in the USA under the fantastically Lovecraftian title The Creeping Unknown).

Watching episodes one and two of the original series, it’s easy to see why it proved so popular with audiences. This was the first of its kind in the UK: a six-part serial and one of the earliest examples of ‘event television,’ a science fiction programme aimed at adults that dealt with its subject of an astronaut returning from space effected by an alien encounter with an intelligence that seemed to go against the grain of giant radioactive insects and rubber-suited monsters. They are also very well acted, with the BBC utilising the multi-camera setup that, until then, was used mainly in the States for comedy shows like Amos and Andy, a trend that would continue for the filming of sit-coms to capture and gauge audience’s reactions to the lines being delivered.

Reginald Tate’s central performance as Professor Bernard Quatermass displays a more humanitarian side to the character than Brian Donlevy’s arrogant, unscrupulous portrayal in Hammer Studios’ feature length remake. When faced with the unexplainable (an unnerving scene wherein Quatermass discovers that Victor’s bone structure has changed), he confesses to “always being secretly afraid that sometime something would happen that I couldn’t deal with.” His statement carries the unnerving sense of helplessness that comes from reading one of Lovecraft’s tales of the Elder Ones, reducing humankind to little more than mere specks of cosmic dust.

With each episode attracting growing viewing figures (climbing from 3.4 million to 5 million in six weeks), it didn’t take long for Hammer Films to see the cinematic possibilities in Kneale’s story, and the studio bought the rights for a £500 advance. Director Val Guest rewrote the screenplay with Richard Landau, condensing the story to fit into a feature length running time by focusing on the horror aspect of returning astronaut Victor Carroon (a great performance by Richard Wordsworth) as he absorbs the life force of living organisms all around him (including a cactus plant) and rapidly mutates into an alien. The effects by Hammer's SFX make-up guy Phil Leakey are pretty gruesome for their time, forcing the BBFC to award the film an X certificate for its violence. Proving as popular with cinema-goers as the serial did with television audiences, the film single-handedly prompted Hammer to begin producing the horror and science fiction films it soon became famous for (until then the studio produced mainly period films and comedies of little note. For instance, Guest’s directing assignment for Hammer before Quatermass was The Men of Sherwood Forest in 1954. In keeping with their reputation for period pieces whilst simultaneously embracing their new direction, the following two decades would see Hammer churn out seven Frankenstein pictures, nine featuring Dracula, and four featuring the Mummy, alongside adaptations of The Hound of the Baskervilles (1958), The Phantom of the Opera (1962) and their own takes on Stevenson’s Jekyll and Hyde). Further, rather than making the cuts that would ensure The Quatermass Experiment would be accessible to a wider (i.e. younger) audience, Hammer celebrated its X certificate, retitling their version The Quatermass Xperiment as a second dare to audiences who had already been terrified by the TV series.

So what makes the film adaptation so great? Well, firstly, in Donlevy, we have a version of Quatermass who isn't the most likeable of protagonists, a man who willingly risks the lives of three astronauts by sending them out into the farthest reaches of space in the name of scientific progress. At one point he callously tells Caroon’s wife, "Personal feelings have no place in science." He isn’t the lantern jawed heroic professor of US creature features and he doesn’t have a love interest to distract him from the task at hand. He’s very much an island, and when he walks off into the night at the end of the picture, we’re left with the feeling that his conscience hasn’t been troubled by his actions. In fact, we feel pretty certain he’ll continue to progress science any way he sees fit and casualties be damned.

Second and last, The Quatermass Xperiment has a quintessential Englishness that taps into the climate of post-war England that things aren’t quite what they used to be. The threat the populace thought was vanquished with the defeat of the Nazis was beginning to resurface in other ways, with rising juvenile crime and the cloud of nuclear threat. Such topical concerns were a fixture of 1950s B-pictures in the States, but in England they were subjects that were seldom broached. What made Kneale’s story so disturbing was that the horror refused to be confined to the outer reaches of space. It was here in England in the form of a human going through an unexplainable transformation, a meteorite crash landing on a village green in Quatermass 2 (broadcast in 1955 and adapted by Hammer in 1957), and, in Quatermass and the Pit (broadcast in 1957 and adapted by Hammer a decade later), a marrying of genres that saw "fantastical futurisms become haunted folklore."

The impact that the first Quatermass outing, both on TV and film, had on audiences and future masters of the macabre cannot be overemphasised. Its influence is apparent in such milestones of sci-fi horror as Doctor Who (first broadcast by the BBC in 1963), 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (see a creepy ‘found footage’ scene which has an astronaut walking up a cylindrical wall), The Thing (1982), The World’s End (2013) and, erm, The Incredible Melting Man (1977).

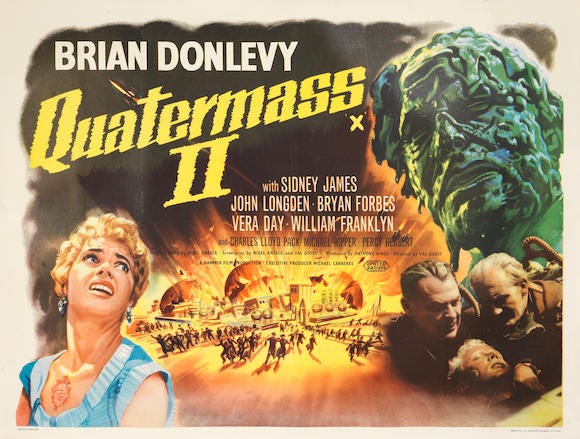

Quatermass II/Enemy From Space (1955/1957)

For Hammer’s second Quatermass outing, Kneale chose to write the screenplay with director Val Guest after voicing his disappointment in the first film. Like the two films that bookend it, Quatermass II deals with contemporary fears (that old favourite of classic sci-fi, Cold War paranoia, best addressed in Don Siegel’s 1956 classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers, of which Quatermass II sometimes resembles), but here the action is pushed to the fore, culminating in a tremendously explosive climax that lays on buckets of slime.

It’s a solid film with a more urgent tempo than its predecessor, moving along at a breakneck pace and reimagining Quatermass (played by Brian Donlevy again) as more of a heroic figure trying to make amends for his unscrupulous behaviour in the first film. Herein lies the problem: Donlevy doesn’t suit this new look; he’s too gruff to be wholly convincing as the hero and nothing like what audiences expected a man of science to look like, which may be a good thing, offering up an alternative to the usual hero-scientist they’d become accustomed to.

Retrospectively, Quatermass II’s influence can be seen on Larry Cohen’s The Stuff (1986), with its concerns over processed food, and the aliens disguised as government officials in V (1983-85), but at the time it got lost in a multitude of other science fiction ‘message’ movies that were doing the rounds. Still popular enough to satisfy its backers, it was nevertheless seen as something of a failure financially when compared to Hammer’s other big production of 1957, The Curse of Frankenstein. With the success of the latter film steering the studio in the direction it became famous for, plans to adapt the third Quatermass outing the following year were temporarily shelved, and it would take another decade for Quatermass and the Pit, the jewel in the Quatermass crown, to make it to cinema screens.

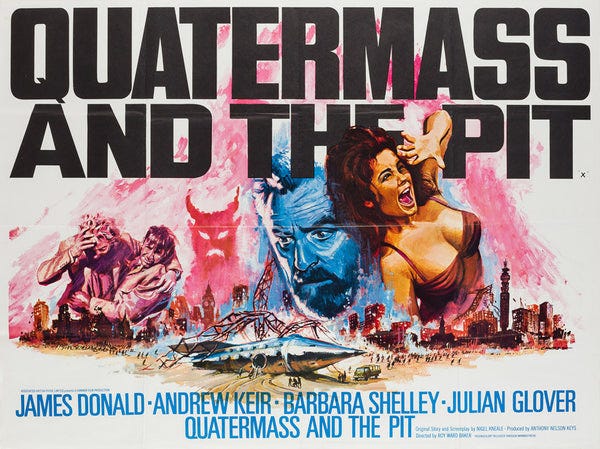

Quatermass and the Pit/Five Million Years to Earth (1958/1967)

Like the films of Jack Arnold, in particular The Incredible Shrinking Man (1955), and classic paranoid thrillers like Invasion of the Bodysnatchers and The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Kneale’s Quatermass trilogy taps into a nation’s unease at feeling that there has been a shift in the paradigm in post-war England. There’s an uncertainty that runs throughout them. What happened to the astronauts during that fifty-seven hours in The Quatermass Xperiment? Are our leaders all they seem, or could they be plotting our downfall as in Quatermass II? And, most intriguingly in Quatermass and the Pit, How long have aliens been laying dormant beneath the streets we tread daily?

An even more generic (and better for it) Quatermass picture than the first two instalments, here Quatermass (played by Andrew Keir) feels duty bound to investigate the unearthing of ape-like skulls and alien insectoids during construction work on an underground station. Keir makes for a much more likeable Quatermass than Donlevy, and here he’s accompanied by stock characters like the palaeontologist who sides with Quatermass’s theory that the skulls are millions of years old and of alien origin, the clueless Colonel Breen, whose logical mind and ingrained xenophobia prevent him from fully comprehending the discovery being anything other than German related, and the impossibly attractive palaeontologist’s assistant, played by Hammer favourite Barbara Shelley.

The first Quatermass to be filmed in colour, it has a wonderfully garish tone and feels more like a true Hammer production than its predecessors. Director Roy Ward Baker could not have been gifted a better screenplay for his first assignment for Hammer. Adapted by Kneale from his own television serial, Quatermass and the Pit throws science fiction, mythology, English folklore and horror into the mix in what is essentially a supernatural detective story that could have sprung from the pages of one of William Hope Hodgson’s Carnacki the Ghost Finder stories. Baker handles the action expertly, filming a panic stricken public running from something (we don’t yet know what), and counting amongst their numbers Quatermass himself. When Quatermass stumbles and looks back in terror, he’s become one of us, and in that moment Donlevy’s Quatermass becomes even less suited to the role. As good as Keir is in this role, it would have been interesting to bring Donlevy back for a third time just to see him break under the pressure of everything he’s witnessed over the series thus far. Compared to the first two films, the threat in Quatermass and the Pit is so unfathomable because we haven’t witnessed its landing on Earth like the astronauts in The Quatermass Xperiment or the meteor in Quatermass II; How long have these beings lay dormant and what (un)earthly presence has summoned them?

Far superior both thematically and artistically than anything Hammer had produced up to that point, it led to Baker’s name becoming synonymous with horror, directing such genre classics as The Vampire Lovers and Scars of Dracula for Hammer in 1970, and the portmanteau films, Asylum (1972) and The Vault of Horror (1973) for Amicus. Kneale, meanwhile, would enjoy a growing appreciation of his work for Hammer that began with The Abominable Snowman (1957) and The Witches (1966), a film that would hint at the direction his writing would take in the 1970s.

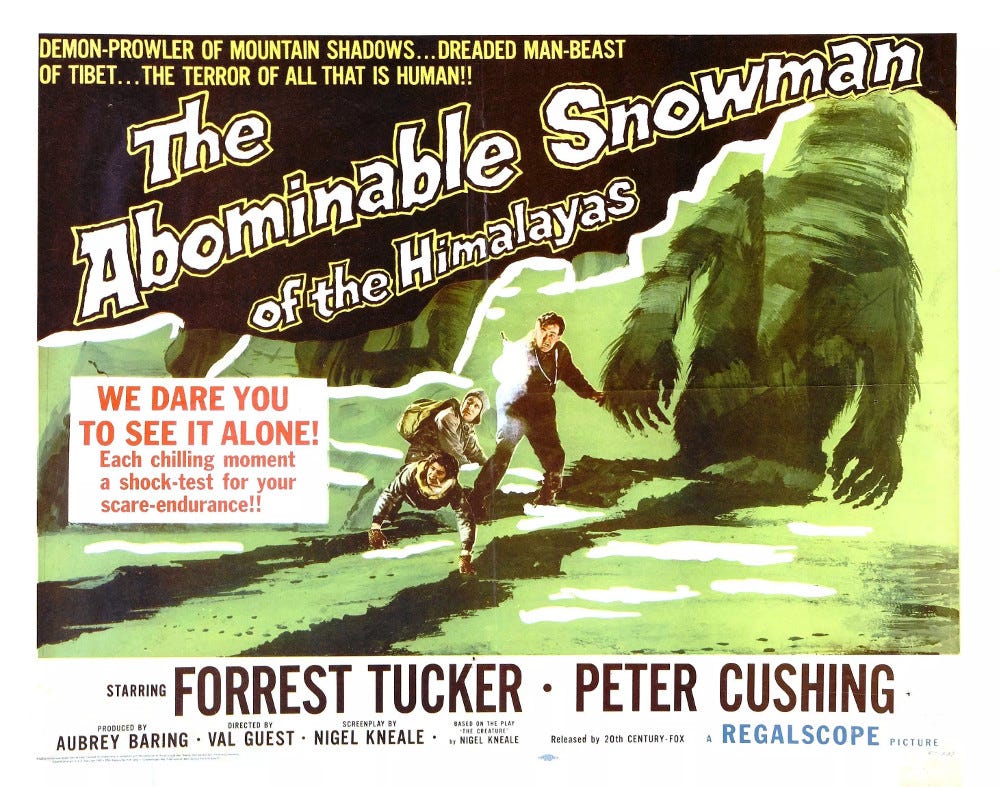

The Abominable Snowman (1957)

Buoyed on by the success of The Quatermass Xperiment, Hammer turned their attention once again to adapting Kneale’s television work, this time his BBC play The Creature, retitled The Abominable Snowman for its theatrical release. Peter Cushing stars as Dr. John Rollason, a scientist who joins Tom Friend’s (Forrest Tucker) expedition into the Himalayas to capture a Yeti. Rollason wants to examine it in the name of science, Friend wants to exhibit it and make big bucks. The two clash while the rest of their party fall prey to the elements and a creature that remains largely heard and not seen. The party consists of a boorish trapper, a photographer and a guide, all of whom are way out of their depth and serve as little more than walking corpses. And that’s fine. Let them drop like flies while Rollason and Friend wax philosophical about the benefits of revealing the Yeti as real to a public ill-quipped psychologically to deal with such a notion. Just don’t expect Hammer horror levels of action once they discover the Yeti, seen here as an almost peaceful creature simply biding its time until mankind renders itself extinct by its own hand.

Inevitably, the film disappointed its target audience and fared badly at the box office, but for those retrospectively familiar with Kneale’s work after the success of Quatermass and the Pit and the questions it raised, it’s worth revisiting to see how his ideas about the directions horror could be taken in were progressing at a rapid rate. The strength of Kneale’s screenplay lies in the focus it maintains on the dynamic between Rollason and Friend. On the eve of the expedition, both men choose to ignore the warnings dished out by the Lama, instead allowing their bull headed ambitions to blind them to the fact that what they may be dealing with could very well finish them off. Rollason is as much an exploiter as Friend, both men believing their own claims that what they’re embarking on is for the benefit of mankind, while what they really mean is that their names will become a by-word for scientific breakthrough and showmanship, respectively.

The visuals compliment Kneale’s script beautifully, Val Guest’s taut direction giving a claustrophobic air whenever the party huddle together against the cold, while the second unit landscape photography allows the audience to reflect for a while on Kneale’s philosophical musings. More existential drama than horror film, it’s more thoughtful in its approach to the Yeti myth than the silly but fun Man Beast (1956), and surprisingly closer to the man-vs-beast concerns raised in Harry and the Hendersons (1987).

The Witches (1966)

Something of a misfire, The Witches is worthy of mention as a precursor to the folk horror boom that took British TV and cinema screens by storm during the 1970s. It also hints at the direction Kneale would take with his exceptional television play Murrain in 1975, and because of that it comes across as something of a warm up for a writer who seemed to be trying to steer horror onto a more subtle, thought provoking path than what Hammer was willing to tread (its failure convinced the studio that Dracula and Frankenstein sequels were the way forward before they jumped on the folk horror bandwagon after the release of Trigon Pictures’ ground-breaking Witchfinder General (1968) and The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971)).

Despite its flaws, The Witches retains its kitsch appeal, thanks to the direction of Cyril Frankel, a director of British comedies like School for Scoundrels (1960) and On the Fiddle (1961), and a finale involving a ritual that’s just plain daft. The weak link, however, is Joan Fontaine in the lead role as Gwen, a teacher recovering in a quaint English village after suffering a nervous breakdown due to an encounter with witch-doctors in Africa (an opening sequence that sets a high bar for the action that follows yet fails to meet expectations). Fontaine always had a ‘fragile’ presence, as though she were about to snap in two once the drama became too intense, so, as far as that goes, she’s ideally cast. But the final act quashes the unsettling feeling the film has been striving for. A better ending would have seen Gwen fall prey to the witch that has held the village under its spell for years, but I suppose Hammer didn’t think horror fans were quite ready for the downbeat endings that would become a benchmark of horror films produced during the increasingly pessimistic 1970s.

The Witches is fairly standard horror fare, but one can’t help thinking there’s a very good film trying to disassociate itself from Hammer’s (by this stage) relatively fresh preoccupation with the gothic. Best watched as a bridge between the Quatermass pictures and Kneale’s stunning television work in the ’70s.

The Stone Tape (1972)

The Stone Tape (dir. Peter Sasdy) is a television play about a team of rowdy computer scientists led by a misogynistic prick played by Michael Bryant. Their research leads to them coming into contact with a spectre. Jane Asher is the computer programmer susceptible to the "other" older spirits who haunt a room in the converted mansion the team use for their research. Using technology to capture proof of the supernatural, they get too close, and things naturally take a turn for the worst.

Of all Kneale’s post-Quatermass output, The Stone Tape is arguably the most influential. Fans of the play include John Carpenter and Guillermo del Toro, and the Doctor Who episode ‘Hide’ is a direct homage, some even considering it an unofficial sequel. It also left its mark on reality TV, especially the ghost hunters in the contrived Most Haunted, with its presenters and experts filling in for the characters in Kneale’s play.

Ahead of its time, the marriage of technology with ancient hauntings that would become commonplace in haunted house films to come (the TV in Poltergeist (1982), the videotape in Ringu (1998) and the camcorder in Paranormal Activity (2007)) was a first here, and cements Kneale’s reputation as a writer who could blend elements of science fiction and folk horror with aplomb. Drawing on Charles Babbage's "place memory" theory that a person's voice leaves an imprint on its environment, Kneale brings Babbage’s theory up to date through the use of computers whilst grounding his story in history and folklore.

It’s fairly pointless to point out the more dated aspects of the play (the blue screen effects are passable but the theatrical acting can become a bit grating), but it’s necessary in order to highlight other aspects of the production like the quality of the production design. The room the spectre haunts is magnificently designed, and the camera lifts above the actors to better view them as hopelessly out of their depth as the sounds they’re trying to record echo off the walls. The strength in Kneale’s writing is letting his characters (arrogant white males who think they know all) reveal themselves as sexist, racist twits so that we can enjoy watching them steadily come apart at the seams once they’re faced with something they can’t get a firm hold on.

Essential viewing for anyone with even a passing interest in British audiences’ burgeoning interest in standing stones and folk horror during the ’70s, or for anyone seeking further proof that Kneale was a writer of the uncanny par excellence. Rightfully regarded as one of his key works, it nevertheless pales in comparison to the play he wrote for ITV: 1975’s Murrain.

Murrain (1975)

Murrain (dir. John Cooper) is the greatest play that didn’t appear on the BBC’s annual series of spooky tales, the excellent A Ghost Story for Christmas. The dictionary definition of Murrain reads as follows:

noun

redwater fever or a similar infectious disease affecting cattle or other animals.

ARCHAIC

a plague, epidemic, or crop blight.

Farming and folklore go hand in hand, the plough unearthing that which should remain buried, as in the skull in The Blood on Satan’s Claw or farmers’ superstitions about blood yolks or planting during a full moon, but Kneale loads the word with extra meaning, drawing from memory its Manx meaning as a curse, specifically one laid by a witch.

David Simeon plays Alan Crich, a veterinarian on his way to visit Beeley (Bernard Lee), a farmer whose pigs have contracted a mysterious illness. Unable to diagnose the problem, Crich is then sent to call on a young boy whose symptoms are similar to that of the pigs. Beeley and the locals who populate the tiny Derbyshire village suspect that something more sinister is afoot and their suspicions point towards Mrs Clemson (an excellent Una Brandon-Jones), whom they believe to be a witch.

Beginning with Crich driving past a quarry before being obstructed by road sweepers as he drives through a crossroads, Murrain is filled with ambiguous moments, always hinting at the horror without ever making it explicit. It’s an opening that draws comparison with the now famous “Duelling Banjos” scene in Deliverance (1972), with the road sweepers and the backwoods country boy both acting as gatekeepers to a world that doesn’t welcome outsiders, especially those who mock their beliefs and lifestyles. It’s this level of ambiguity in Kneale’s writing that drives the narrative throughout its lean 55-minute running time. The locals’ olde English superstitions about witches and how they come to bear on an elderly and persecuted woman gradually hold more weight as the story progresses. Crich, meanwhile, uses a medical man’s logic and compassion to try to convince them otherwise, going as far as to help Mrs. Clemson by buying her food from neighbouring Buxton because the village’s only shop refuses to come into contact with anything the woman touches. When the shopkeeper unwittingly handles the woman’s money she too falls ill, but again Kneale and director John Cooper resist the urge to cut away to Mrs. Clemson and in doing so forge a link between the two, instead implying through Crich that the shopkeeper’s illness is psychosomatic, a symptom of hysteria akin to that which plagued England in the seventeenth century. All the way up to the end, this level of restraint is maintained, never giving the audience the reasoned answer it hopes for nor confirming that the villagers’ superstitious beliefs are grounded in fact. It’s as much about the power of suggestion and hive mentality as it is about superstition, and like the best films, stories and plays that allow events to happen off-screen or approach their horror knowing that the unexplainable is far more unnerving than concrete evidence, Murrain leaves you, not frustrated that your questions haven’t been answered, but actually glad that if you’re permitted to cross the threshold back home with Crich, you’re leaving thankfully none the wiser.

For a longer, more insightful essay into Murrain, read K.B. Morris’s excellent piece for Horrified Magazine.

The Woman in Black (1989)

Kneale’s last significant contribution to the science fiction and horror genre is this, the ITV’s adaptation of Susan Hill’s 1983 novel, The Woman in Black. Benefiting from a limited TV budget, it’s far superior than the Hammer 2012 version that was blighted by tired J-Horror gimmicks.

Starring Adrian Rawlins as solicitor Arthur Kidd, the Edwardian setting and plot ground the story firmly in gothic territory. When Kidd is sent to settle the estate of Mrs. Drablow, a widow who resided at a remote house on the north-east coast of England, he is plagued by the cries of a drowning horse, woman and child as well as appearances from a woman dressed in black (Pauline Moran).

Kneale’s script stays true to the book, only deviating slightly with the ending and adding a scene where Kidd listens to the eerie recordings that Mrs. Drablow made on wax cylinders (Kneale bringing technological advances and voices from the past together again). Director Herbert Wise allows the audience to glimpse the woman in black from afar, just as Kidd would have seen her, and throughout the film we’re side-by-side with him until the film’s tragic denouement.

Less is more here, but only up to a point. And when the jump scare comes, it doesn’t pull any punches. I can honestly say that The Woman in Black contains one of the most frightening scenes in horror, and when it was broadcast at 9pm on Christmas Eve, viewers were understandably terrified but given a reprieve as Kneale included the scene to happen before an advert break. One can imagine that feeling of relief, but also the trepidation at having to go back in once the festive adverts had run their course. The bleak ending didn’t let them off so lightly.

![The Witches (1966) [31 Days of Hammer Horror Review] – BIG COMIC PAGE The Witches (1966) [31 Days of Hammer Horror Review] – BIG COMIC PAGE](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!3xZ7!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fecad5021-1bde-47fa-be81-1e24cb23a472_1200x881.jpeg)

Gorgeous Substack post, also re-kindled the stamp-collector within (always used to get the special editions as soon as they came out from Post Office), pretty sure there was a Universal monster series launched recently?