Haxanvale

A story for Halloween.

It was sometime back in October when Clifford Thorpe asked me to bring his son back home.

I’ve haven’t seen Cliff since. I don’t expect I’ll ever see him again.

He came to me as a friend, broken and desperate and quite unlike the man I had known for all these years. The wealthiest man in the county, Cliff had never asked for anything from anyone. But sometimes all the money in the world isn’t enough to get what you want.

He seated himself next to me on the sofa, turned his bulk to face me and lighted a cigarette.

“I blame that weirdo bitch he’s got himself involved with,” he said, holding out a trembling hand as a makeshift ashtray. “He’s only known her for two months and already she’s got him hooked like a fish.”

I went to the sideboard and found an actual ashtray in the back of one of the drawers. I placed it on the coffee table in front of him.

“I assume you mean Melody,” I said. “I must admit, he has spent most of our last few lessons talking about her. In French, of course.”

I had been tutoring Lucas for eight months now. Cliff had asked me to teach his son French to impress one of his business associates in Quebec.

“At least he talks to you about her,” Cliff said, “in whatever language. The two of them hardly speak a word to me or Marjorie. They just stay up in his room, come down when they want food, and poomph! Gone again.” He took a long pull on the cigarette, wincing at the taste. “You know, Marjorie caught them at it on the living room floor one afternoon. You can imagine her face.”

I could. Marjorie Thorpe. Pillar of the community. Churchgoer. Fund-raiser. Somewhat sanctimonious, and according to Cliff in one of his more lucid moments, as frigid as they come. Or don’t, apparently.

He stubbed out his cigarette. “I don’t even smoke these bloody things anymore.”

“So, why do you think he’ll listen to me, Cliff? I’m his French tutor, not his confidante.”

“Because he like you, that’s why. He used to come home from your classes full of ‘John said this’ and ‘John said that’. He’s always taken your advice over mine, from being little.” He shrugged his wide shoulders. “Nonetheless, I thought I still exerted some influence over him.”

I placed a hand on my friend’s shoulder. “He’ll come around, Cliff. He’s twenty-three, old enough to make up his own mind. I’m sure he’ll come around.”

Cliff stood, took up position awkwardly with one elbow resting on the mantlepiece. It was the spot he’d usually take during parties while he regaled the room with boasts about his latest business venture. Now, he stood naked before me, stripped of his usual assuredness.

“Not this time, John,” he said. “I’ve been to see him. He’s staying with her family. They seem to have as much of a hold over him as she does. He just looked right through me. It’s like they’ve put a bloody spell on him or something.”

“Oh, come on,” I said. “Surely, it’s not that bad, is it?”

“I’m afraid it is, John. You see, I sort of lost it, tried to pull him out of there. Then these blokes, must have been uncles or brothers or something, threw me out into the street. And do you know what I did? I offered to buy him back. Me, lying there in the mud with them laughing at me. And all Luke could do was stand there staring. He didn’t even try to help his old man up. I’m worried I might have lost him, John. I’m scared for him.”

Then Clifford Thorpe, childhood friend, womaniser, fighter, and self-made millionaire, did the one thing I thought I’d never see him do. He wept.

I was at a loss as to what to say. Here was a man who had made himself a constant presence in my life since my wife died last year. A man whose rose-tinted outlook on life I could depend on to brighten my darkest hour with an off-colour joke. And now, all I could do was sit and look at my hands laced in my lap and wish I were somewhere else.

As though he could read my thoughts, he said, “I’m sorry, mate. You’ve been through enough without me prattling on. I better leave.”

“No,” I said, rising. “You’ve been here for me since Linda passed. The least I can do is return the favour.”

Cliff wiped at his mouth with the back of a meaty hand. “Thanks,” he said, avoiding my eyes a little embarrassedly. “I feel like such a fool.”

“Not another word of it,” I said. “Now, let me get us both a drink and you can tell me where to find him.”

While we drank our brandy, Cliff drew a crude map on a piece of lined paper. In spite of his obvious distress, I couldn’t help but smile inwardly. It was as though we were boys again, drawing maps to find imagined treasure.

“Is this really necessary?” I asked. “I do have satellite navigation, you know.”

He didn’t look up from his work. “No good down there,” he said. “It gets you as far as Saltstone, then the signal goes.” He turned the paper so I could see. “Here,” he said, jabbing a finger on an X in the centre of the page.

On either side of the X he’d circled the names of two villages, Saltstone and Tynsdale, names I was vaguely familiar with. Above the X he’d written Haxanvale.

“I’ve never heard of it,” I said.

“I’m not surprised. It’s hardly even a village. God knows why Luke would . . .” He bolted down the last of his brandy. “Well, we all know why. Her.”

I poured him another drink.

“Leave it with me,” I said. “I’ve a couple of appointments I need to keep. I should be able to get away by the weekend.”

“The weekend?” he said. With the glass poised at his mouth his eyes strayed to a point over my shoulder. “No.” His eyes levelled again with mine. “It needs to be tonight.”

“But it’s past noon now,” I said. “It’ll be dark by the time I get there.”

“Please, John. Here, I can pay you.”

He pulled out a money clip from his inside jacket pocket. There must have been at least five hundred pounds. I held up my hands.

“No,” I said. “Listen, if it means that much to you, I suppose I can always cancel my appointments. I don’t think the French language is going to change overnight, is it.”

“Thanks,” he said, stuffing the money back inside his jacket. “You’re a true friend, John.”

“As are you,” I said.

We stood and shook hands.

“I’ll never forget this,” he said.

Once he’d left, I fished around in the garage for an old A-Z of the West Country. I scanned the index for Haxanvale but found nothing. I located Saltstone and Tynsdale and traced my fingers along the road markings. Where Clifford had marked an X on his map, there was only space.

Why would Lucas, with luxury flats in Knightsbridge and St. Andrews, as well as the family home here in Bath, choose to relocate to a place that didn’t even warrant the attention of an A-Z?

With a red pen, I marked the space with an X, and got ready to leave.

#

I chose not to cancel my appointments for the following day, hoping to make the four-hour journey there and return before midnight. Whether I succeeded in convincing Lucas to accompany me home was another matter. He had always been accustomed to getting his own way, a privilege afforded him by the elite circles he moved in.

As I backed out of the driveway a feeling of trepidation mixed with excitement passed over me. I had no idea who these people were or how they were going to welcome me. But then maybe it was time for me to regain some of my sense of adventure. Linda would have been proud to see me playing the hero.

I took the road that led to Penzance. Driving against the traffic, I found myself making good time. Enjoying the drive and the accompanying Bach on the stereo, I decided to try a circuitous route.

After driving for two hours I pulled into a layby and unwrapped the sandwiches I’d prepared earlier. I had no doubt that Haxanvale would have a pub where I could eat something on my arrival. However, my suspicion of country folk, a supposition based on repeated viewings of Hammer horror films, made me wary of eating anything cooked by such people.

As I continued on my way, my Sat Nav informed me I would be arriving at Saltstone in less than an hour. From thereon I would have to rely on directions from one of the locals.

#

On the outskirts of Saltstone, I came to a petrol garage. I parked at a pump on the forecourt. On the pump was a sign reading Please Ask For Assistance. I turned to see a woman squinting at me from inside the shop. I signalled for her to come over. She was long and thin with grey wiry hair tied up in a severe bun.

“Afternoon,” she said. “How much will you be needing?”

“You might as well fill her up,” I said.

She gave a strange smile which remained in place while she began fuelling.

“I’m sorry,” I said, “have I said something to amuse you?”

“You called your car ‘her’,” she said. “Sounds funny, that’s all, you making sure your car knows its place.”

“Just a figure of speech. Nothing intended.”

She pulled the nozzle out of the tank, placed it back on the pump. “You can pay inside. We take card or cash, but I’d prefer cash. The machine charges me a fee for the privilege.”

Inside, she took her place back behind the counter. A young girl, no more than six years old, stood beside her. She clutched a tattered looking doll to her chest. Her wide eyes peered out at me from behind an unkept fringe of yellow hair.

I added two chocolate bars to the cost of the fuel.

“Sorry,” I said. “I’ll need to pay by card. I like to make sure I’ve cash on my hip.”

In entered my pin into the card reader. Wordlessly, the woman handed me my receipt.

It was then that my peevishness reminded me of how I could stop a conversation dead with Linda by trying to up-stage her.

I slid one of the chocolate bars across the counter. “Here,” I said, “for your daughter.”

“I teach her not to take from strangers,” the woman said.

“Very wise. Perhaps you can resell it then. Make up for the loss on the card reader.”

When she made no move to take the chocolate bar or thank me, I bid her good day and walked to my car.

The first drops of rain started as I pulled out of the forecourt. I paused for a moment, deliberating whether I should go back inside to ask for directions. Preoccupied with the power play I’d found myself in, I’d completely forgotten to ask.

When I checked my rear-view mirror, I saw the little girl standing at the edge of the forecourt. She was eating the chocolate bar and cradling the doll in the crook of her arm. With her other hand she moved the doll’s arm back and forth, waving me goodbye.

I eased off the brake and rounded the corner to Saltstone.

#

The sign welcoming me to Saltstone boasted of a population of one-hundred-and-twenty-three. It was like any one of the hundred other tiny villages that dotted the landscape. I passed a pub, a shop and post office, and four rows of cottages.

No sooner had I driven passed the Welcome sign, I found myself approaching the Now Leaving sign, beside which a man wearing a raincoat pulled a small dog away from the road. I stopped, wound down my window, and asked him the way to Haxanvale.

He bent with his head partially inside the car. I was surprised to see how well-groomed he kept his beard and moustache.

“You want to go straight ahead for another mile or so,” he said. “When you reach the T-junction you take a left. You’ll find it down a dirt road on your right.”

“Is it the only dirt road?” I asked.

“You’ll know it by the car on the verge. Knackered. No wheels.”

“No wheels?”

“That’s what I said. Without a driver, there’s no need for wheels, is there?”

There was something about how these people spoke that rankled me. I was about to say something in response, when he said, “What business do you want in Haxanvale?”

“My own,” I said.

“Suit yourself. But if I were you, I’d keep on for Tynsdale.”

And without bothering to explain why he thought I should bypass Haxanvale, he pulled his dog away from the car and made his way back towards Saltstone. I fought an unexpected urge to follow him.

“Smart arse,” I said, but only once I’d rolled up the window.

I followed his directions and, sure enough, I soon saw the abandoned car, raised on wooden blocks and standing out in the rain like a relic from the past. It looked as though it had been sitting there for a while; the first signs of rust had already formed around the wheel arches, and there was moss and leaves gathered at the base of the windscreen.

I guided my car down the narrow road that led to Haxanvale. The road was badly maintained, and I bobbed and bounced over potholes as low-lying branches slapped at the roof of the car. As the late afternoon light became dimmer, I occasionally veered into the tracks laid by previous, heavier wheeled vehicles. My tyres, balding and ill-equipped for such roads, fought for purchase in the mud. I moved forward a little faster than I’d have liked, getting the ridiculous notion that I was being drawn in, that my say-so in anything from here on amounted to nought.

The road ran for quite some time. Now that my trusted Sat Nav had given up on assisting me, I estimated that I’d been driving for a further mile when the first lights of the village blurred into view.

My descent had caused the landscape to rise around me. Haxanvale, as its name suggested, was placed firmly in the belly of a valley.

It was then, with my destination in view, that my car dropped down sideways into a ditch. My seatbelt dug into the side of my neck as my car jolted to a halt. Fortunately, the ditch was on the passenger side. I climbed out of the car, holding the door open with one hand to prevent it swinging back into my shins. When I let go it slammed shut behind me. A dozen birds, small and black in the murk, alighted a tree.

I surveyed the situation and saw it was hopeless. The car was almost at a right angle with the back end raised slightly higher than the front. Any attempt at driving it out would only cause the rear wheels to spin redundantly, them barely touching the surface of the ground. I cursed and slammed a palm down on the bonnet. As I trudged down the road, I braced myself for the humiliation my asking for help would bring.

#

Haxanvale consisted mainly of a court yard surrounded by cottages. There was a hall and a pub, but no sign of the shop selling the newspapers that might have connected it to the outside world. Lights glowed from inside the cottages and through the windows of the pub. Under different circumstances it might have looked welcoming.

I followed the sounds of voices to the pub.

What I found inside didn’t match the image I had of a cosy countryside inn. Absent was the open fire, the wooden beams, and the low lighting one usually expects to find. In their place was an electric bar heater, a flat-pack bookcase holding cheap ceramic ornaments, and one fluorescent ceiling light that hummed as it cast its glare over the entire room. The kind of atrocious, dated wallpaper one would expect to find in a teenager’s bedroom ran half the length of one wall, the black and white checked pattern ending abruptly, as though the decorator hadn’t had quite enough rolls to finish the job properly. Where the wallpaper ended, the brickwork had been painted over in grey without being plastered first. The tables, six in all, looked flimsy enough that they could collapse at any moment. The accompanying chairs, made from the same metal and plastic as the tables, were akin to those you’d see stacked in the corners of community halls. The whole scene was quite depressing, and I realised then that here lived the truly poor and marginalised in society. Progress had left Haxanvale behind, yet still it breathed unapologetically, short of breath yet resilient.

There were only a dozen or so patrons seated in two small groups, each one male with a pint of lager in front of him. Half of them were smoking, displaying a lack of respect for both common law and the health of others. As I walked to the bar, not a one of them paid me any mind.

Behind the bar was a man of muscular build with a weather-worn face. His hair was peppered with grey and cropped close enough to the skull to show off the scars that criss-crossed at the bump above his forehead. In one ear he wore a stud earring. His other ear was missing its lobe. Trying not to stare at his deformity, I scanned the options in drink available to me. As with the rest of the pub, my hopes for countryside comforts were left wanting. There were two optics, one with vodka, the other scotch, and both with labels displaying brands I’d never heard of. There were two pumps on the bar, giving a choice of either lager or cider. A small fridge held one flavour of bottled alcoholic pop and a plastic bottle half filled with orange cordial. Cola and lemonade, carbonated and syrupy, came from the post-mix dispenser attached to the bar.

Without greeting, the barman, whom I assumed to be the landlord, asked me what I wanted. Not what I wanted to drink, only what I wanted.

“I’ll have a lager, please,” I said.

Somebody behind me made a farting noise with their mouth. I chose to ignore it, noticing the smile that played at the corners of the landlord’s mouth. He took a half-pint glass from under the bar.

“This do you?” he asked.

“A pint would be better,” I said.

He raised his eyebrows, replaced the glass with a pint pot and placed it under the pump. He poured without tilting the glass and still the lager refused to develop a head.

“That’ll be a fiver,” he said.

“Five pounds for a lager?”

He stopped pouring. “I can stop half way if you want. Then it’ll be only three pounds.”

Another fart sound at my back, followed by one or two snickers and the sound of the door opening and closing.

“No, you can keep on pouring,” I said. “I can afford it.”

“I’ll bet you can,” the landlord said, pulling down on the pump.

I paid him with a ten-pound note and turned to face the room with drink in hand. I noticed that one of the men had left.

I took a sip of the lager and turned back to the bar.

“I was hoping you’d be able to help me,” I said. “I’m afraid I’ve got my car stuck on the road coming in. Do you have a tow bar or anything?”

“I can have some of the lads here take a look.” He gave a short whistle through his teeth. “Bill, Marvin. Help the man, will you?”

I turned my attention back to the room. Two men seated at one of the tables rose together and left the pub.

I started to call after them. “Do you need me to . . .”

“They’ll be alright,” the landlord said. “It’ll be sorted it for you.”

I rested an elbow on the bar. “Thanks.”

“No need. Now. You still haven’t answered my question. What do you want?”

“What makes you think I want anything?”

He didn’t answer.

“Well,” I said, “it sounds a bit forward, but I’m here to talk to Lucas. Lucas Thorpe? His father sent me.”

“Sent you to do his bidding, did he?”

“Well, not quite that. He’s a friend, you see. A good friend. I owe him a lot.”

“You’re in his debt, then.”

“I wouldn’t put it like that either.”

“How would you put it?”

I leaned back from the bar. “Listen, I just want to talk to Lucas. If he’s around, I’d appreciate it if I could have a few moments with him. That’s all. I don’t plan on staying longer than I need to.”

There was the sound of heavy feet tramping up the cellar steps, and a thick-set woman, breathless, panting, and red in the face, appeared from out of the floor. She had her sleeves rolled up. A pink scar running the length of one forearm stood out against skin darkened with smears of brown freckles.

“The barrel’s changed,” she said to the landlord. “Next time you can bleeding do it.”

She clutched at his crotch. He slapped her hand away. Said, “Cut it out. I’ve the hag tonight, not you.”

The woman shrugged. “Perhaps I better look elsewhere then.” She smiled in my direction. “And who might this be?”

“He’s after Lucas,” the landlord said.

“Good luck,” the woman said. “I’ve been after him since he arrived here, but he’s never away from Melody’s side.”

“Then perhaps I can talk with both of them,” I said.

The landlord folded his arms across his broad chest. “Anything you’ve got to say to Melody, you can say to us.”

The door behind me opened again and I turned to see Bill and Marvin approaching the bar. They were accompanied by two other men, younger than themselves. All four of them were splashed with mud up to their waists.

One of the men, who I later learned to be Marvin, said, “We’ve got your car out of the ditch. It’s outside.”

I breathed a sigh of relief. “Thank you all so much.”

“Never a problem.”

They stood two on either side of me.

“The garage would have charged you twenty quid for towing it,” one of the younger men said. “Call it a tenner so’s we can get a pint apiece, and that’ll do.”

I started to laugh, but the sound caught in my throat.

“I wasn’t expecting to have to pay,” I said.

Marvin placed a hand on my shoulder. “We can always stick it back in the ditch.”

The others looked at me, waiting for an answer. I took out my wallet and handed a ten-pound note to the landlord. I didn’t dare question why he’d overcharged me.

“Let me see to these gentlemen,” he said, “then you can tell me what you want with Melody and her boy.”

“I’d prefer it if I could speak to them alone. It’s quite a personal matter, you see.”

The woman snorted. “Don’t the parents count for anything where you come from?”

“Of course, I’m sorry,” I said. “I didn’t realise. You’re . . .”

“Daddy,” the landlord said, pulling the first pint. “This here’s Melody’s Mum.”

“Then perhaps we can all talk together? I wouldn’t mind that.”

“See, Roy,” Marvin said. “He’s giving you permission.”

The landlord, Roy, glared at him. “Shut your stinking hole, Marvin,” he hissed.

Marvin looked down at the bar. Roy fixed his eyes on me.

“Two minutes while I sort these drinks out, then we’ll talk.”

I felt a prickle at the back of my neck.

While he poured the pints in silence, the woman bit at a piece of torn skin on her thumb. When it started to bleed, she put the thumb in her mouth and began sucking. She looked up at me with her head lowered, trying for coquettish and failing miserably. I averted my eyes, my cheeks burning.

The man who had left the room earlier returned. The rain beat at his back as he swung the door open.

“The hag’s ready when you are, Roy,” he said.

“Keep her dosed up,” Roy said, his eyes still fixed on mine. “I’ve got a meeting to go to.”

“But you said . . .”

Roy’s eyes flicked to a point over my shoulder. “I know what I said, Sam,” he shouted. “Now be on your way, keep her dosed up, and shut the bloody door!”

The man gave a second’s pause before going back out. The door closed with a slam.

“Right then,” Roy said, putting the last of the pints on the bar. “Shall we go and have that chat now?”

He didn’t make it sound like a question.

#

Roy lifted the serving hatch on the bar, and I walked through. The woman walked ahead of me, leading me into a back room. I could feel Roy’s breath on the back of my neck.

She flicked a light switch and the room was illuminated by a naked bulb. The room was furnished as a living space, with a two-seater sofa and armchair, a small coffee table, and a bookcase crammed with worn, tattered paperbacks, most of them with their spines facing the wall. There wasn’t a television and the carpet was a dated blend of burgundy and purple patterns. A staircase behind the sofa led off to upstairs.

“I’ll go and fetch them,” the woman said.

As I watched her climb the stairs, Roy unfolded a garden chair and motioned for me to sit down. He flopped down in the armchair facing me. I thought of things to say but was afraid anything I did say at this point would sound false. Nice place? Your wife seems very friendly? Your pub’s very welcoming?

In silence we listened to the muffled exchange of voices on the other side of the ceiling.

When the woman came back down the stairs, she was followed by a young girl dressed in a short floral dress. She was pretty with ginger hair curling around her shoulders. Lucas, trailing behind her with his head down, held onto her hand.

The three of them sat down on the sofa with Lucas in the middle. His hair, once styled and treated, had been cut short, crudely and without thought. The brown cords and plaid shirt he wore were a far cry from the expensive, tailored clothing I was used to seeing him in. The clothes were ill-fitting, hanging off him in folds. I guessed they might have belonged to Roy. On his feet he wore a pair of slippers, two sizes too small so his heels touched the carpet.

I tried to hide my shock.

“Hello, Luke,” I said, rising to shake his hand. “How have you been?”

He looked at Roy, who gave him a short nod. Lucas took my hand limply by the fingertips. There were plasters on the back of each of his hands.

“So,” I said, sitting down again. “Your Dad came to see me today. He thought we could have a chat, see if you might want to come back with me for a couple of days. Maybe come back here again some other time. What do you think?”

“Tell him, Melody,” Roy said. “Tell him what Lucas thinks.”

Melody might have been the prettiest girl I’d seen in a long time, but when she looked at me, I felt a chill run down my spine. There was something behind her stare, something ancient, unnameable. She had the eyes of an old woman.

“I don’t think he wants to go anywhere with you, John,” she said. “But then again, I can’t say I’m overly fond of keeping him here. I’ve had my fill.”

I didn’t recall mentioning my name once since I’d arrived. I swallowed and wondered if anyone had noticed the lump bobbing up and down in my throat.

“What’s up?” the woman said. “I thought you wanted to talk.”

“Well,” I said, “I do, but I have to admit I wasn’t expecting to have to go through an interpreter. Can you not speak to me, Lucas? What’s wrong?”

“Tell him, Melody,” Roy said. “Tell him what’s wrong with Lucas.”

“Tongue tied,” Melody said. “Show him.”

Lucas opened his mouth wide. There was a thread of copper wire wound tightly around his tongue. The tip had blackened. Blood stained the bottom row of his teeth. He made a small choking sound.

“My God!” I cried, jumping to my feet.

Roy reached under the cushion of his chair, pulled out a pistol, and levelled it at me.

“Sit back down, John,” he said. “Sit down now or I’ll shoot you right in your stinking belly.”

“Jesus,” I said, lowering myself down onto the chair. “Jesus God.”

The woman laughed, slapping a hand down on Lucas’s knee. He flinched at her touch.

“Please,” I said, “I don’t want trouble. I just want to take Lucas and go, and you’ll never hear from us again.”

My voice was shaking. I sounded weak and insincere.

“You’ll stay,” Melody said. “She says we can have him instead now, Dad.”

“We’ll see,” Roy said. “Why don’t you take Lucas back upstairs with you. Let the grown-ups talk for a bit, eh?”

Melody pouted, stood and yanked Lucas up by his hand.

“Come on, cunt,” she said. “Time for bed.”

After they’d left the room, Roy leaned forward, his elbows resting on his knees, the gun pointing at the floor. “Go and make us all a cup of tea,” he said to the woman.

She said nothing in return. Just left the room by a door leading to the kitchen.

“So, your friend,” Roy said, “Cliff, isn’t it? What did he tell you about us?”

I said, “Please don’t kill me.”

Roy smiled. The first time I’d seen him do so since I arrived in this God-forsaken place. “Don’t be stupid. I’ve never killed anyone in my life, and I’m surely not going to start now. But I can hurt you though. I can do that much. So, you tell me what he told you, and I’ll try and restrain myself, how’s that?”

I gritted my teeth, held my jaw tight. I was afraid I’d cry once I started talking.

“He told me that you turfed him out. Not you I don’t think, but two other men. That . . . that he offered you money for Lucas, and you laughed at him.”

“That’s it?”

I gave three short, jerky nods. The muscles in my neck strained to stop my head from shaking.

Roy rubbed at his chin with the barrel of the pistol.

“Hm. Money. For as long as I’ve had family going back here in Haxanvale, money’s never been that important. We deal in trade, see? Help us out with something we’re lacking in, and we’ll try and do the same for you. A bit old-fashioned in today’s climate, but there it is.”

“How do you know my name?” I asked.

“Because your friend told us.”

“Then you were expecting me.”

He nodded, slowly, easily, seeming to enjoy watching the penny drop. “Trade,” he said.

Oh, Cliff. Why?

The woman came in carrying a tray with three mugs of tea and a plate of biscuits. A cosy gesture to help us all settle in, made warped and perverted by the situation at hand.

“Tell you what,” Roy said. “You drink your tea while I explain a few things. You deserve that much before we move on.”

The woman sat down on the sofa. “Help yourself to a Jammy Dodger,” she said, stuffing a biscuit into her mouth.

Roy said, “Right, I’ll get the sad news out of the way first. It upsets us, but it needs telling.” He reached across and patted the woman on her knee. “Melody had a sister, younger by a year. Blossom. She’d always been the restless type, a bit dreamy. Wanted more than Haxanvale could offer her, felt like she was missing out on something without knowing what it was. We don’t believe in television here, John. Too many adverts trying to make you buy shit you don’t need. Too much fakery. So, when Blossom reached seventeen, she thought she’d find out for herself. We tried to convince her to stay. Had to tie her to the bed a few times, didn’t we, love?”

The woman nodded, her eyes never leaving mine.

“In the end, she snuck out from under our nose. Hitch-hiked her way north, wound up in Bath. Met your friend Lucas, who introduced her to your friend Cliff, who introduced her to lots of his rich, older friends. She spent a lot of time at one of his clubs. The Exchange?”

I drew in a ragged breath.

“You know it, then.”

“Yes.”

“Ever go there yourself?”

“No,” I lied.

I had been to The Exchange once, not long after Linda died. Cliff insisted it would do me good. There were girls there putting on shows behind a one-way mirror while men watched, drank and closed deals. Eventually, a group of them would enter the room and exert their power. If there was only one girl in the room, they would take turns. Some, however, didn’t have the patience enough to wait their turn. I vowed never to return, and Cliff never mentioned it again.

“You’re lying,” Roy said.

In a flash, he hit me in the throat with the side of his hand. The pain was excruciating.

“Don’t do that again,” he said. “If there’s one thing I won’t tolerate it’s a liar.”

The woman rubbed at the scar on her arm.

“Anyway, they bought her nice clothes, jewellery. Took her to swanky restaurants. But she soon saw through it all. You can take the girl out of the country, but you can’t take the country out of the girl, John. So when she tried to leave, they made it difficult for her. She’d seen too much, you see. Dirty fucking politicians getting up to God knows what. They couldn’t risk her blabbing off. And she would have done. I’d have made sure she went to the police. Not that they would have listened to our kind.” He sighed, as though he were preparing himself for what he had to say next. “They got her hooked on expensive drugs, the kind of shit you can’t trade a bag of veg for.” He wiped at a tear that had sprung loose from his eye. “Don’t tell anyone you saw me crying, will you, John.”

I shook my head.

“Thanks,” he said, reaching for his tea. “Your drink’s getting cold.”

I reached for my mug with a shaking hand. The tea was weak. Too milky, too sweet. But it was warm, and my aching throat welcomed it.

“In the end,” Roy continued, “Melody offered to go and find her. I forbade it, of course. I’d already gathered enough men around me for us to go up there and take her by force. But she made me see sense. Showed me how violent it would become, how I’d end up being arrested, charged. She has a certain power does Melody. Uses some of the old magic passed down by the hag. I give the hag what she needs, and she teaches Melody all she knows. It’s a simple trade. So, I trusted her to bring Blossom home to us. But she was too far gone. Even the magic couldn’t reach her. So instead, Melody brought us back a token.”

My voice was a whisper. “Lucas.”

Roy held out his hands. “We have to make our own entertainment down here, John. Much like your friend in Bath. Lucas didn’t want to join in at first, but Melody soon brought him around. Still, as you know, children can get bored of their toys so quickly. Always wanting something new to entertain them.”

My head began to swim as Roy came in and out of focus. I heard his voice as though he were talking to me through a broken transistor.

“When your friend Cliff came, we let him entertain us for a bit. Some of the younger kids rode him around like a pig. He looked funny, all fat and sweaty, but his heart wasn’t in it. Kids can sense these things.”

A voice from somewhere behind me said, Sleep.

“He’s slipping,” the woman said.

“Yeah,” Roy said. “I think it’s time.”

My eyes followed him as he raised himself from the chair.

“I’ll go and see to the hag,” he said.

I blacked out.

#

I remember the horror in flickering images, a projection lit somewhere deep in my memory.

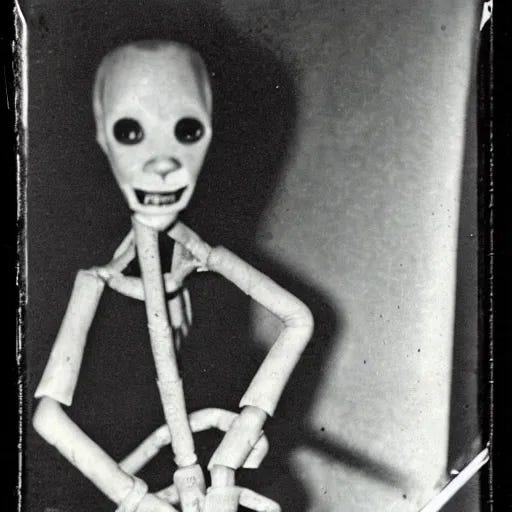

I remember being sat on a stool. I was on a stage in a large hall with people sitting in rows of chairs. They were all staring at my nakedness. At the sight of me opening my eyes, one or two of them began clapping. Taking this as their cue, the others followed suit. Soon the whole room was standing in applause.

I think I tried to stand then but my legs wouldn’t hold me. It was then that I became aware of the pain. I looked down at myself, saw eye-screws embedded in both of my knees and in the backs of my hands. Attached to the eye-screws were copper wires, pulled taut by children sitting in rafters above me. They were giggling, relishing the control as they worked me like a puppet. The macabre dance they had me perform brought gales of laughter from the audience.

I must have screamed then because a hand clapped over my mouth. Through the fog I remember Roy’s face close to mine. There was a putrid smell coming off his palm, and he said something about the hag’s sex.

Melody stood by her father’s side. She was holding hands with a stooped figure; an old woman, emaciated and withered, but with eyes belonging to a girl much younger.

The hag.

I twisted my head away from Roy’s hand. Pain shot through my knees and the backs of my hands, as my limbs were pulled up and down and left and right, and I screamed again, not only through the pain but at the madness of it all.

I remember the sounds of stamping feet and clapping hands, the audience mimicking my moves while they whooped and laughed.

I can’t say for sure how long the performance lasted for, but through it all I remember silently pleading for mercy as I stared wildly into Melody’s eyes. But they were as cold as the grave, grey and lifeless, without thought or emotion.

It was in the clear and beautiful eyes of the hag that I found pity. They penetrated me, searching my soul, finding the good that was still there.

The voice, from man nor woman, came from somewhere inside of me.

Run.

The screws tore my flesh as I threw myself off the edge of the stage. A number of those in the first row rose to grab me. Roy’s voice bellowed, forcing them back into their seats.

“Let him go, she says! Let him go! We must all be held accountable!”

I scrambled to my feet, slipping in the blood that had begun to leak from my wounds. Heads turned to witness my exit as I ran up the aisle and through the doors of the hall.

When the rain hit me, I shouted into the black of the night. From the shadows only silence answered me.

I searched the court yard for my car and found it gone. I located the foot of the lane that had led me to this terrible place and ran across the cobble stones until I felt mud beneath my feet.

Adrenaline pushed me up the hill and onto the road, but it was the fear at my back that kept me running.

I remember the sign for Saltstone and a man with a moustache and beard.

I remember warmth and humanity.

I remember his voice.

“Everything will be alright now. Help is on its way.”

I prayed for it to be true.

#

All were held accountable. Everyone who played a part had to face what they’d done.

The law came down hard on Clifford Thorpe, but his arrest served only to appease the public. Those he entertained bought their anonymity, and with it their freedom.

When they found Lucas in the toilet of a petrol station, the blood from his wrists had pooled across the tiles and leaked under the door. They found my car abandoned a mile back.

I was kept under observation while they tried to heal my mind, but the nightmares kept my sanity at bay.

Arrests were made in Haxanvale, though it was suspected that I may have acted as a willing participant. The concoction they found in my system, matching the powder in the jars in the kitchen, was made up of nothing more than natural ingredients. The added element that put me under came from somewhere else. It was a place no one dared to look.

I never spoke about what they did to me. The humiliation was too great. I felt as though they were relieved when I became mute.

My scars are explanation enough.

Let me remain in silence.

THE END