Enys Men

Mark Jenkin's Enys Men and the films that inspired a film that's impossible to pin down.

When I read in Sight & Sound that writer-director Mark Jenkin had curated a season of short films, features and television programmes that inspired his second film, Enys Men, it was as though somebody had laid a corn doll gift at my door. Having already watched the accessible “Unholy Trinity” of Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973), I found myself developing a need to explore the British films and television plays that helped develop that uniquely English sub-genre known as ‘folk horror.’ Preceding Jenkin’s announcement, a number of books simultaneously began to find their way to my door, as if they were urging me to dig deeper; books on legends of the British Isles, the Mabinogion (which served as inspiration for Alan Garner’s The Owl Service), Diane Purkiss’s The English Civil War and William Harrison Ainsworth’s The Lanchashire Witches, along with three exemplary contemporary novels, The Manningtree Witches by A.K. Blakemore, The Loney by Andrew Michael Hurley, and The Woodwitch by Stephen Gregory, and an obscure out-of-print curio, The Corn Dolly, a 1976 children’s novel by Margaret Elliot. I didn’t consciously seek out these books, they were just suddenly there, and during a period wherein folk horror had made a slow but steady return to cinema screens, thanks in large part to the films of Ben Wheatley, Ari Aster and Robert Eggers.

Before Kill List (2011), A Field in England (2013), Hereditary (2018), Midsommar (2019), and The VVitch (2015), however, folk horror had returned to ground after enjoying a particularly fertile run throughout the 1970s. In its absence, the slasher film took over cinemas, spawning ever more tiresome franchises that inevitably imploded in a series of meta-horrors. Occasionally, it would rear its head in films like The Blair Witch Project (1999), an ingeniously conceived project that used the now widely imitated ‘found footage’ formula and a marketing campaign that listed the actors in the film as still missing. It didn’t feel like it belonged with the glut of pre-millennial horror films that incorporated the CGI violence and knowing winks that only served to distance the audience from ever being truly scared. Instead, The Blair Witch Project played on the uncertainty that what you were watching may actually be real. That uncertainty, the lack of concrete knowledge that is the foundation of the eerie, soon gave way to a deeply unnerving feeling. I haven’t felt that way about a film since, and though Midsommar came close, as did Kill List, the violence in both soon overshadowed the feeling of disquietude felt in the early stages of the films. With Enys Men, however, the disquietude remains throughout.

First off, Enys Men is not a horror film, or at least not in the way we’ve been taught to recognise a horror film. There are no jump scares, cheap tricks, or ludicrously exaggerated ways to kill dumb disposable characters. However, it is bordering on folk horror, despite claims by some critics that it doesn’t really fall into that category either; I’ve heard it described as a metaphysical psycho-drama, and Mark Kermode labelled it, simply, a “Cornish film,” which is probably nearer to the mark, but he also said, correctly, that to try to understand it diffuses the experience. So why bestow a label on it at all when ambiguity can instil a much more unique reading in the mind of the viewer. The fact that it’s impossible to pin down exactly the kind of film it is, is what makes Enys Men such a memorable experience.

Set in 1973 on a remote Cornish island (Enys Men, pronounced Enys Main, is Cornish for “Stone Island”), an unnamed wildlife volunteer (Mary Woodvine) is given the task of observing a rare flower and recording its development. Isolated, she experiences visions of both the island’s and her own past. She is also visited by a boatman, though you’re never sure whether this is happening in the present, or if it’s another of her memories taking form as time begins to fold in on itself. She discovers the ghosts of miners below, while Bal Maidens (female manual labourors who also worked in Cornwall’s mining industry) inhabit the island aboveground. Atop a rise, a menhir (an upright standing stone) is the first thing she sees when she opens her front door in the morning. As darkness falls, the moonlight gives it an etheral quality. In a wide shot early in the film, we see her walking along the rise, disappear behind the stone, and for an instant that I can’t fully explain, I had the uneasy feeling she wasn’t going to come out the other side. The moment is revisited towards the end of the film, and I’m still at a loss as to how exactly Jenkin managed to make me react in such a way to something so innocuous as a woman walking past a stone. The film is filled with moments like this. There’s a perpetual foreboding that brought to mind Nicholas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now (1973), a certain dread that something is either happening or is about to happen, but when and if it does, we’re not going to be given the comfort of a rational explanation.

This is a film of image and sound. There is very little dialogue (as should be expected from a film with only one principal character), and when there is, it’s usually a thought out loud or the disembodied voices coming through the transmitter that links the woman to the mainland. Jenkin’s brutal, jagged editing splices together extreme close-ups of faces, rocks, teapots and lichen, with wider shots of the island, the sea, and the house at once giving the sense of something closing in and watching from a distance. Jenkin’s decision to shoot on 16mm colour film with a Bolex camera makes the whole thing look like a rough-hewn document lost to time. That it only invites questions where we were hoping to find answers makes it all the more disquieting. It really is extraordinary filmmaking.

So, what Jenkin calls the DNA of Enys Men are the films of various length and medium that he’s chosen to share through the British Film Institute. After watching Enys Men, it’s apparent which have had the clearer influence, though they are all embedded in the fabric of his film in one way or another. And, unsurprisingly, as it happens, there are few that can be labelled pure horror. Some of the feature films he’s included are Nicholas Roeg’s Walkabout (1971), Peter Strickland’s Berberian Sound Studio (2012), David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997) — a fever dream not unlike that endured by the woman in Jenkin’s film — and Long Weekend (1978), an Ozploitation gem that shares Enys Men’s underlying message that the land is sentient, and definitely not to be fucked with. One film not included in the season is John Carpenter’s The Fog (1980), though Jenkin does make mention of the similarities between the scenes showing the discovery of a piece of broken, lettered driftwood. These are all fine films, but of the features, it’s Ben Rivers’ incredible black and white film Two Years at Sea (2011) that has left its stamp on Enys Men’s use of sound and image.

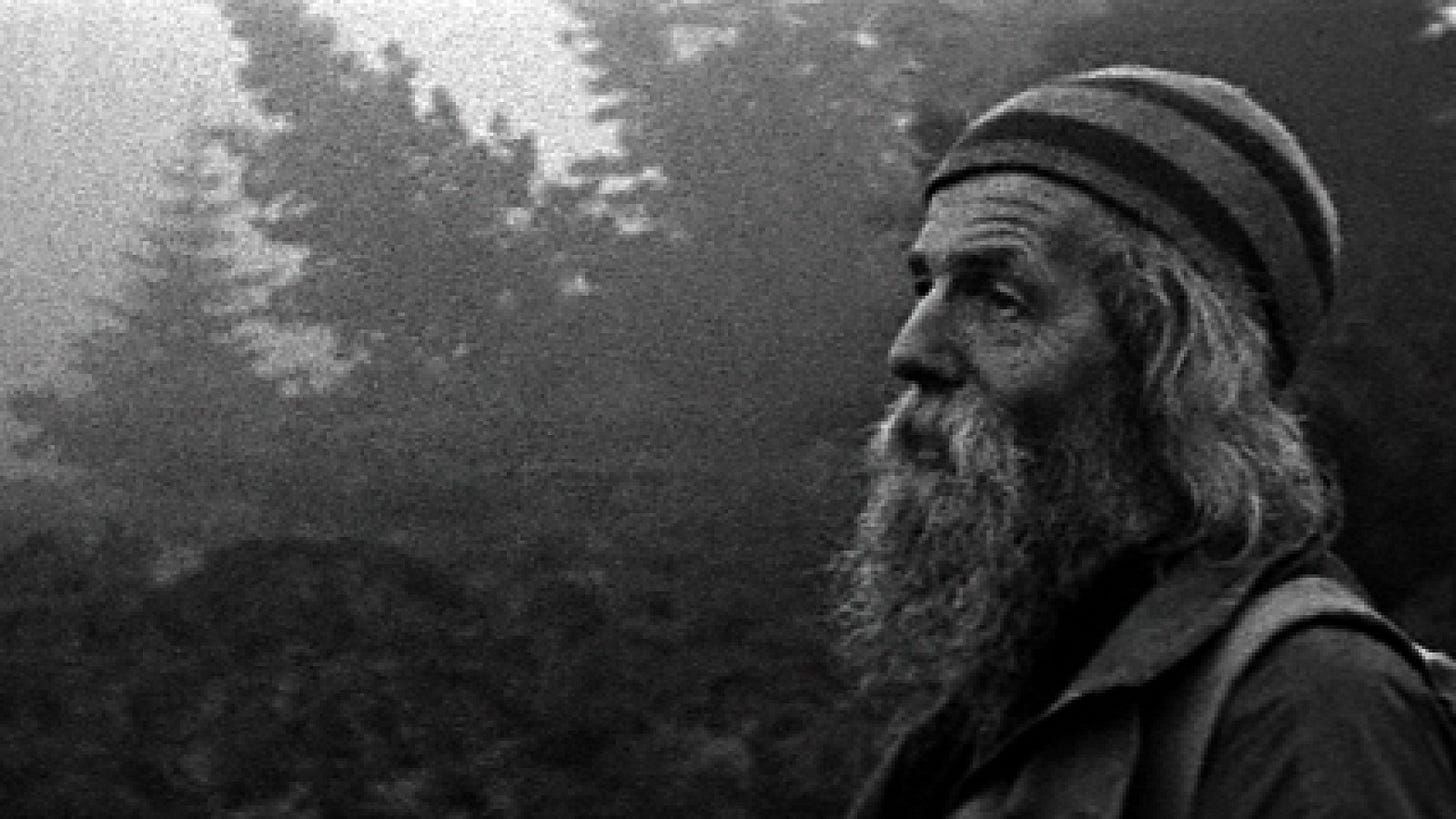

Like Jenkin, Rivers shot his documentary about Jake Williams, a man who shunned modernity to live in remotest Scotland, on a 16mm Bolex camera and hand processed the film himself. Held up as an example of ‘Slow Cinema,’ Two Years at Sea has next to no dialogue, the occasional burst of diegetic music, and very long takes in which nothing appears to be happening. Yet, something is happening. All the time. Just watching someone be without explaining how they got where they are or where they came from is a factor in Enys Men’s story. The obvious difference between the two films is that Jenkin’s is a work of fiction, and so clues, no matter how ambiguous, need to be dropped in for the narrative to work. Rivers’ film, on the other hand, doesn’t call for explanation, yet the aesthetic is the same.

Of the short films, Wind (1999) is a highlight. Written and directed by Jenkin’s fellow Cornish native Bill Scott, it’s twelve minutes of pure invention, deploying modelwork and rear projection to tell a funny, virtually dialogue-free story about an incident at a lighthouse. Its influence may not be explicitly evident in Enys Men, but it did inspire Jenkin enough to realise that he could make films in and about his neck of the woods entirely on his own terms.

Second to Wind is Oss Oss Wee Oss, a short documentary filmed in Padstow, Cornwall on Mayday 1953. Directed by Alan Lomax and narrated in semi-rhyme by Charlie Bate of Padstow and Charlie Chilton of London, it’s an affectionate look at a fertility and resurrection ritual, filmed with the utmost respect for its subject. In contrast to the hustle and bustle of Lomax’s film is Derek Jarman’s Journey to Avebury (1973), a series of shots of the surrounding countryside and home of the largest megalithic stone circles in England. Taken as a whole, aspects of all three films are present.

But of all the films Jenkin appears to have revisited with Enys Men, none are more apparent than those produced for television throughout the 1970s and into the early ’80s. Of these, the films Lawrence Gordon Clark produced for the BBC’s A Ghost Story for Christmas feature prominently: his adapations of M.R. James’ A Warning to the Curious (1972) and Charles Dickens’ The Signalman (1976), and, more noticeably, his final film for the series, Stigma (1977).

A departure for Clark, Stigma was the first of the films in the series that was neither a period piece or an adaptation of a classic ghost story. With its modern (for its day) setting and focus on body horror, it’s easy to draw direct parallels between Clark’s film and Enys Men.

After the removal of a large stone unearths the remains of a witch, a wife and mother begins to bleed profusely from tiny pinpricks in her skin. The ordeal she undergoes is similar to that of the woman in Enys Men, whose own scarred body begins to grow lichen as it mirrors the flower she’s been observing. Stigma also has not one, but two strong female protagonists, another departure from the male-dominated tales that came before it. Males are reduced to onlookers and, like the boatman who comes and goes in Enys Men, the husband in Stigma is shunted into the background while his wife is forced to suffer alone.

Finally, Penda’s Fen, Alan Clarke’s 1973 Play for Today scripted by David Rudkin, is the most complex of all Jenkin’s choices. A somewhat confusing blend of social commentary, critique on rural masculinity and folk horror, it’s as engaging as it is frustrating. Yet that more than explains why its ambiguous appeal has found its way into Enys Men’s DNA. Jenkin freely admits to prioritising feeling over understanding (he also cites Robert Bresson as an influence), and it’s to our benefit as cinemagoers that he’s following the paths laid down by Roeg, Clark, Robin Hardy and Nigel Kneale, while treading them side by side with Wheatley, Aster and Eggers.

******

Outside of Jenkin’s selections, I’d also recommend the following:

The Owl Service, an eight-part adaptation of Alan Garner’s children’s novel, originally broadcast over the winter of 1969-70.

The aforementioned “Unholy Trinity” of Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and The Wicker Man (1973).

Children of the Stones, another eight-part series for children, filmed in Avebury, Wiltshire, and broadcast in 1977.

Any or all of the following films and plays scripted by Nigel Kneale: The Quatermass Xperiment (1955), adapted by Hammer Films from Kneale’s six-part television series for the BBC; Quatermass II (1957); Quatermass and the Pit (1967); The Witches (1966); The Year of the Sex Olympics (1968); Murrain (1975); and The Stone Tape (1972) — this last entry is the only one of Kneale’s works selected by Jenkin.

The following Ben Wheatley films: Kill List (2011); Sightseers (2012); A Field in England (2013); In the Earth (2021).

Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), directed by Ari Aster.

Two short films by Robert Eggers: Hansel and Gretel (2007) and Brothers (2015); and his first two features, The VVitch (2015) and The Lighthouse (2019).