An edited copy of an article that sums up British film noir:

"Generally defining where film noir starts, stops and what it is – and perhaps more importantly, what it isn’t – is hard enough. Getting what’s specifically film noir in British cinema is even more elusive. This is even if we narrowly stick to when it was most likely to have happened: postwar, between 1945 and the arrival (at the start of the ‘60s) of British cinema’s much better known ‘kitchen sink’ realist filmmaking movement.

We are dealing with a genre heritage amongst whose interesting characteristics might be that it’s long been assumed not to exist. We are also dealing with a British screen culture that’s often enjoyed wallowing in another famous notion of British cinema’s non-existence – and the greatest ever put-down of any national cinema, by director Francois Truffaut, in 1962, to Alfred Hitchcock: '… Isn’t there a certain incompatibility between the terms “cinema” and Britain (national characteristics, the subdued way of life, the stolid routine) that are anti-dramatic, in a sense?'

Perhaps Truffaut’s boiling scold is a starting point. Perhaps a reminder also of facts of which Truffaut seemed almost in willful denial: that his Hitchcock was both British and a film noir specialist. It’s not that British cinema doesn’t exist. It’s rather that it’s just a bit like one of those snotty juvenile delinquents that often inhabit its film noirs: grievously misunderstood by a lack of inquiry into its sociology.

British cinema noir is important because it is the best place to start, if you do plan on revising pre-conceived opinions about the nature of British cinema’s existence. Not just because film noir is so often a good place to start (anywhere, in any national cinema), as the genre where you’re always most likely to find the veiled symbols of social criticism. But also because, at least after 1945, British cinema’s own film noir cycle is the best place to go to see the smouldering social revolt against everything Truffaut complained about."

(Credit: Quentin Turnour, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

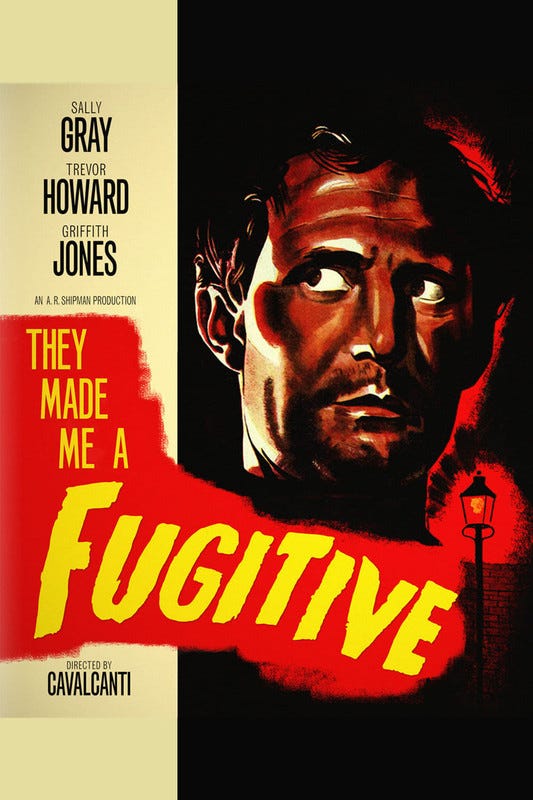

They Made Me a Fugitive (dir. Alberto Cavalcanti, 1947)

A British film noir starring Trevor Howard as Clem, a down at heel RAF pilot whose involvement in a bungled heist leads to him being framed for the manslaughter of a policeman and seeking revenge. Co-starring Griffith Jones as psychotic gang boss Narcy, and Sally Gray as the moll turned good, the entire cast, from the three leads to the supporting players is exceptional, particularly those who make up the rest of the gang and a small but significant role by Vida Hope as the dead-eyed and put-upon wife who gives Clem shelter at a price.

With some surprisingly violent scenes for a film of this era (an expertly staged and prolonged fight scene involves head-butting no less, a definite no show for the BBFC), and clear references to Narcy being a cocaine addict, this is a hard-as-nails glimpse into London's underworld, with Clem embodying two classic noir figures: the returning, disillusioned war hero and the wronged man.

Directed by Alberto Cavalcanti, who helmed the 'ventriloquist' segment in Dead of Night (1945) -- by far the highlight of the anthology -- and shot by Otto Heller, whose many credits include The Ladykillers (1955), Peeping Tom (1960) and The Ipcress File (1965), this is a somewhat overlooked film. The Dartmoor countryside and city streets look as bleak as you'd expect from a noir. There's a claustrophobic air blanketing the scenes in the gang's hideout, and Narcy's wired face looking direct into camera as he dishes out his punishment also make for some brutally effective shocks.

It Always Rains on Sunday (dir. Robert Hamer, 1947)

More a precursor to 1960s kitchen sink realism than film noir, It Always Rains on Sunday nevertheless bears some of the style and themes to earn it a place in the pantheon of British noir. It's also been compared to the poetic realism movement in 1930s French cinema, due to its focus on the working class and low-end criminality.

Set over the duration of a day, the Sandigates, a family of five, become the epicentre of a series of events which stem from the secrets that threaten to shatter their lives. Rose, fifteen years younger than her husband, is mother to a young boy and stepmother to teenage girls. Clearly unhappy with the humdrum life she leads, she finds an old flame rekindled when her ex-fiance Tommy Swann breaks out of prison and hides out in the family air-raid shelter. Angus McPhail's script interweaves multiple plot strands, including one daughter having an affair with a married man while the other is groomed by a local spiv whose schemes bring him into contact with three struggling criminals and the law. Each life, from Rose down, is doomed to fail through bad choices and the fall-out from WWII; the story is set in Bethnal Green, a deprived area that saw rationing and derelict buildings take their toll on otherwise resilient residents. Because of this, sympathies lie with almost every character, especially Rose and her husband George.

A film that finds depth beneath the surface of the everyday, the stolid predictability of routine leads each character (except for George) on a search for something more. But it's the lack of options that make this great noir; there's a hopelessness hanging over everything, and all we can do as viewers is watch as things slowly slide towards the inevitable final reel.

A favourite of Martin Scorsese, it's likely that the criminals on the take and fractured family unit had some influence on both Mean Streets (1973) and his remake of Cape Fear (1991). Just a thought.

Fun fact: the film was based on the debut novel by Arthur La Bern, whose 1966 novel Goodbye Piccadilly, Farewell Leicester Square was the basis for Alfred Hitchcock's 1972 serial killer flick, Frenzy.

Night and the City (dir. Jules Dassin, 1950)

Jules Dassin had already broken new ground in 1948 with the police procedural/noir The Naked City, and went on to film the ultimate heist movie, Rififi in 1955. In between came Night and the City, a film noir he shot in Britain during his exile from America after the House Un-American Activities Committee accused him of taking part in communist politics. The desperate, urgent and very pissed off tone of the film reflects this, Dassin's mood encapsulated by Richard Widmark's breathless, hyperkinetic performance.

Widmark is always worth watching when he's at his craziest (Kiss of Death (1947) and Pickup on South Street (1953) remain two films I've watched over, thanks largely to his performances in them), and here he's perfect for the role of Harry Fabian, a con man whose determination to succeed matches his apparently natural ability to fail. Fabian acts like a man possessed, moving at a frenetic pace from one scheme to the next until he inevitably finds himself getting in way over his head.

At times Widmark, like Fabian, needs reigning in, and his overacting can become a bit too much, but he's anchored by some fine supporting players, especially Gene Tierney as the girlfriend who suffers his get-rich ideas, Googie Withers as the scheming wife of nightclub owner Phil (the great Francis L. Sullivan from David Lean's Dickens adaptations), and Herbert Lom as a Russian enforcer.

The London setting is great for highlighting how lost Fabian is in a city peopled with loose associates who take great pleasure in watching this cocky American fall (an unfortunate English trait that draws comparisons with the HUAC and their attempts to knock film stars off their lofty perches).

Definitely a product of the circumstances it was made under, this is stone cold, unsympathetic noir.

Obsession (a.k.a. The Hidden Room (dir. Edward Dmytryk, 1949)

Like Jules Dassin, who made 1950's Night and the City in Britain after being exiled from Hollywood, Edward Dmytryk (one of the "Hollywood Ten" who fell foul of McCarthyism) also turned to England to make this film noir.

Robert Newton stars as Clive, a respectable doctor whose wife, Storm, pushes him one step too far after he discovers her having yet another affair. Bill is the unlucky sap who just happens to be the "next one" in line and the focus of Clive's experiment in carrying out the perfect murder.

A good film that could have been far better, Obsession suffers from a captive-captor dialogue between Clive and Bill that isn't wholly convincing. The set-up should have created a series of taut and claustrophobic scenes, but Bill isn't nearly panic-stricken enough to make his situation believable. The cast, which also includes Sally Gray as Storm and Phil Brown as Bill, are fine, and Dmytryk's skill at directing noir is as strong here as it was on Murder, My Sweet (1944) and Crossfire (1947), but without that darker edge, the film falls short of being a great British noir, and instead turns out to be a routine but still quite satisfying thriller.

Fun fact: actor Phil Brown would go on to play Uncle Owen in Star Wars.

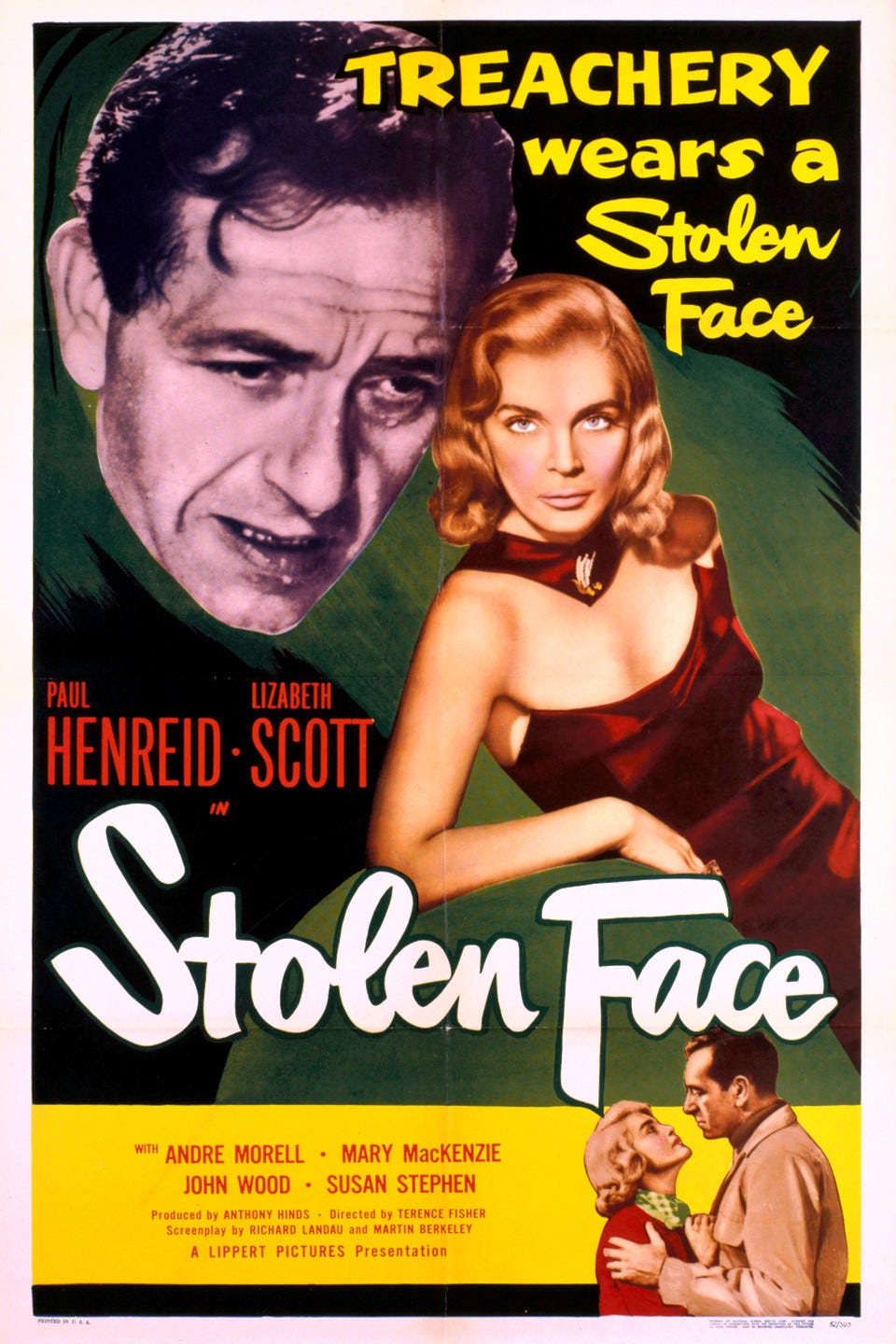

Stolen Face (dir. Terence Fisher, 1952)

(Spoilers ahead)

Stolen Face is a "quota-quickie" British B-film produced by Hammer as part of a cross-Atlantic distribution deal with Robert Lippert, a business relationship that would lead to Hammer's first foray into SF-horror with The Quatermass Experiment in 1955. There is a hint of the macabre that Hammer would become synonymous with here, but Stolen Face is essentially a film noir which can also be seen as a precursor to Vertigo (1958).

Lizabeth Scott plays Alice, the unobtainable obsession of plastic surgeon Dr. Phillip Ritter (Paul Henreid), who sees an opportunity to literally mould another woman into her appearance when habitual thief and stinking drunk Lily (Mary Mackenzie) seeks his help. Cue Lizabeth Scott again, this time as Lily, and some very unscrupulous behaviour from Dr. Ritter, who almost matches Vertigo's weirdly obsessive Scottie and his "oh well, she'll do for now" disregard for human feelings.

You could be easily fooled into thinking Lily is the bad apple in this love triangle, and it's true that she's a terrible person, is a total embarrassment in public, and thinks nothing of stealing fur coats and fooling around behind Ritter's back, but the real villain here is Ritter: within hours of imposing on a poorly Alice in a bed and breakfast, he uses his position as a doctor to pull back her bed sheets and examine her before sulking over her not agreeing to marry him after only being acquainted for 48 hours. When the ending comes after a very Hitchcockian set piece on a train, poor Lily becomes a disposable footnote to Ritter's diabolical scheme, while he smugly walks away with Alice, the woman he desired all along.

A great picture that zips along at a cracking pace, and could have been titled 'Skin Deep' or the more cruelly appropriate 'You Can't Polish a Turd.' Director Terence Fisher, who would go on to direct a string of Hammer Horror classics throughout the '50s and '60s, was clearly right at home helming this twisted little tale.

Odd Man Out (dir. Carol Reed, 1947)

A strong contender for one of the best British films ever made, Odd Man Out stars James Mason as the Organisation man dying and on the run in an unnamed Northern Ireland city.

A film about the "troubles" without mention of the IRA or Belfast, this is an exceptional film, incorporating Greek tragedy, poetic realism, neorealism and film noir, the latter aspect due to Robert Krasker's high contrast cinematography. Like The Third Man, every shot is a piece of art; you could pause this film at any given moment and frame the shot on your wall.

Performance-wise, Mason is on fine form as Johnny McQueen, an almost mythological figure in the eyes of the kids who replay his shoot-outs with the cops, and the residents who peer from behind closed doors to avoid being questioned by the law. It's significant too that we hear his voice first before we see him, as though we're expected to recognise Mason's distinctive whisper as McQueen's own.

The supporting cast of rogues and do-rights who try to either harbour or hinder Johnny along the way are as central to the story as Johnny himself, yet though he takes up relatively little screen time, his presence is felt in the conversations that circle his whereabouts and the alleys and side streets that run with the rain.

There are too many other things that are great about this film to cover here, but the hallucinations that Johnny sees as a result of blood loss and fever are something you rarely, if ever, see in contemporary mainstream cinema; the two stand-outs being a floating gallery of portraits and a vision of people he knows appearing in the bubbles of a spilled beer. The snowfall towards the end of the film is beautifully lit too.

If Carol Reed hadn't topped his own achievement with The Third Man in 1949, Odd Man Out would be rightly considered the best British film noir of the '40s. As it stands, it'll have to make do with taking second place.

These reviews originally appeared on my Instagram page @filmfolkuk